Summary

The standard definition of temperature homogenisation is of a process that cleanses the temperature data of measurement biases to only leave only variations caused by real climatic or weather variations. This is at odds with GHCN & GISS adjustments which delete some data and add in other data as part of the homogenisation process. A more general definition is to make the data more homogenous, for the purposes of creating regional and global average temperatures. This is only compatible with the standard definition if assume that there are no real data trends existing within the homogenisation area. From various studies it is clear that there are cases where this assumption does not hold good. The likely impacts include:-

- Homogenised data for a particular temperature station will not be the cleansed data for that location. Instead it becomes a grid reference point, encompassing data from the surrounding area.

- Different densities of temperature data may lead to different degrees to which homogenisation results in smoothing of real climatic fluctuations.

Whether or not this failure of understanding is limited to a number of isolated instances with a near zero impact on global temperature anomalies is an empirical matter that will be the subject of my next post.

Introduction

A common feature of many concepts involved with climatology, the associated policies and sociological analyses of non-believers, is a failure to clearly understand of the terms used. In the past few months it has become evident to me that this failure of understanding extends to term temperature homogenisation. In this post I look at the ambiguity of the standard definition against the actual practice of homogenising temperature data.

The Ambiguity of the Homogenisation Definition

The World Meteorological Organisation in its’ 2004 Guidelines on Climate Metadata and Homogenization1 wrote this explanation.

Climate data can provide a great deal of information about the atmospheric environment that impacts almost all aspects of human endeavour. For example, these data have been used to determine where to build homes by calculating the return periods of large floods, whether the length of the frost-free growing season in a region is increasing or decreasing, and the potential variability in demand for heating fuels. However, for these and other long-term climate analyses –particularly climate change analyses– to be accurate, the climate data used must be as homogeneous as possible. A homogeneous climate time series is defined as one where variations are caused only by variations in climate.

Unfortunately, most long-term climatological time series have been affected by a number of nonclimatic factors that make these data unrepresentative of the actual climate variation occurring over time. These factors include changes in: instruments, observing practices, station locations, formulae used to calculate means, and station environment. Some changes cause sharp discontinuities while other changes, particularly change in the environment around the station, can cause gradual biases in the data. All of these inhomogeneities can bias a time series and lead to misinterpretations of the studied climate. It is important, therefore, to remove the inhomogeneities or at least determine the possible error they may cause.

That is temperature homogenisation is necessary to isolate and remove what Steven Mosher has termed measurement biases2, from the real climate signal. But how does this isolation occur?

Venema et al 20123 states the issue more succinctly.

The most commonly used method to detect and remove the effects of artificial changes is the relative homogenization approach, which assumes that nearby stations are exposed to almost the same climate signal and that thus the differences between nearby stations can be utilized to detect inhomogeneities (Conrad and Pollak, 1950). In relative homogeneity testing, a candidate time series is compared to multiple surrounding stations either in a pairwise fashion or to a single composite reference time series computed for multiple nearby stations. (Italics mine)

Blogger …and Then There’s Physics (ATTP) partly recognizes these issues may exist in his stab at explaining temperature homogenisation4.

So, it all sounds easy. The problem is, we didn’t do this and – since we don’t have a time machine – we can’t go back and do it again properly. What we have is data from different countries and regions, of different qualities, covering different time periods, and with different amounts of accompanying information. It’s all we have, and we can’t do anything about this. What one has to do is look at the data for each site and see if there’s anything that doesn’t look right. We don’t expect the typical/average temperature at a given location at a given time of day to suddenly change. There’s no climatic reason why this should happen. Therefore, we’d expect the temperature data for a particular site to be continuous. If there is some discontinuity, you need to consider what to do. Ideally you look through the records to see if something happened. Maybe the sensor was moved. Maybe it was changed. Maybe the time of observation changed. If so, you can be confident that this explains the discontinuity, and so you adjust the data to make it continuous.

What if there isn’t a full record, or you can’t find any reason why the data may have been influenced by something non-climatic? Do you just leave it as is? Well, no, that would be silly. We don’t know of any climatic influence that can suddenly cause typical temperatures at a given location to suddenly increase or decrease. It’s much more likely that something non-climatic has influenced the data and, hence, the sensible thing to do is to adjust it to make the data continuous. (Italics mine)

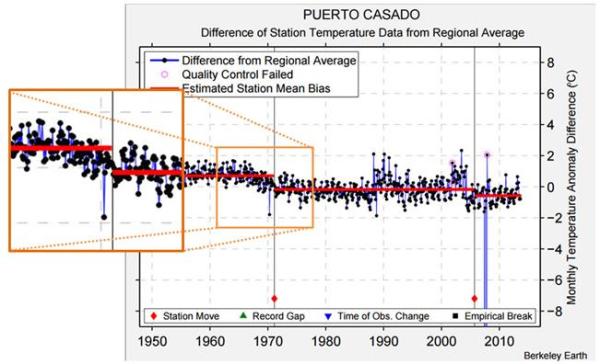

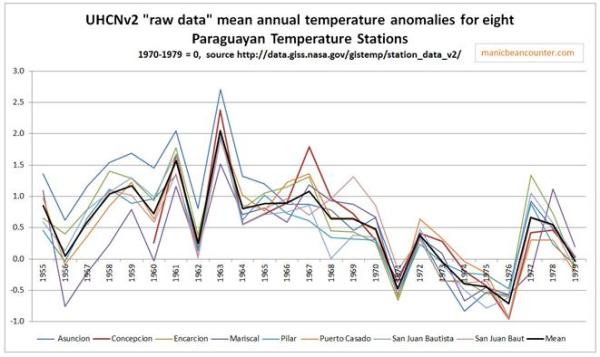

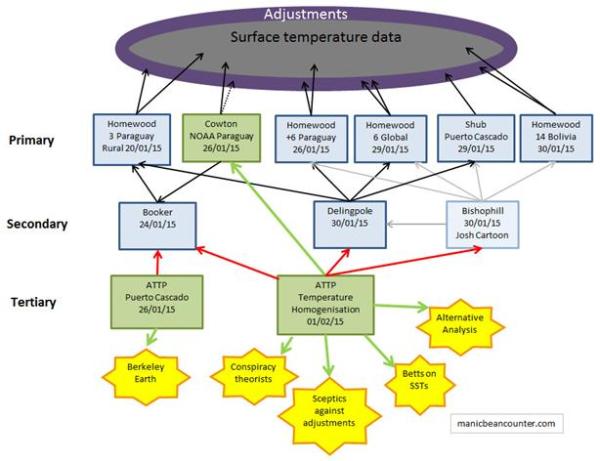

The assumption of a nearby temperature stations have the same (or very similar) climatic signal, if true would mean that homogenisation would cleanse the data of the impurities of measurement biases. But there is only a cursory glance given to the data. For instance, when Kevin Cowtan gave an explanation of the fall in average temperatures at Puerto Casado neither he, nor anyone else, checked to see if the explanation stacked up beyond checking to see if there had been a documented station move at roughly that time. Yet the station move is at the end of the drop in temperatures, and a few minutes checking would have confirmed that other nearby stations exhibit very similar temperature falls5. If you have a preconceived view of how the data should be, then a superficial explanation that conforms to that preconception will be sufficient. If you accept the authority of experts over personally checking for yourself, then the claim by experts that there is not a problem is sufficient. Those with no experience of checking the outputs following processing of complex data will not appreciate the issues involved.

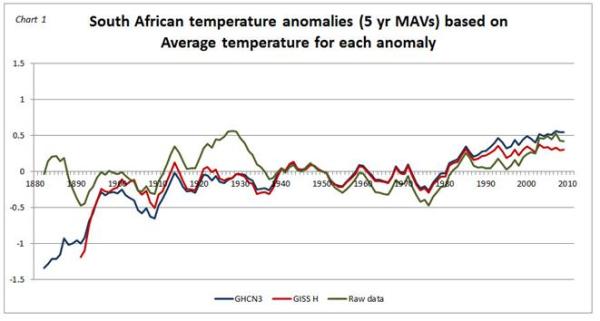

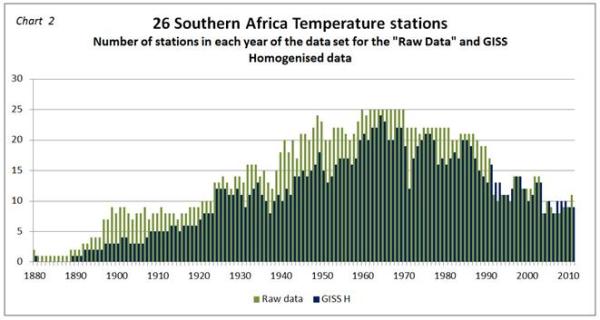

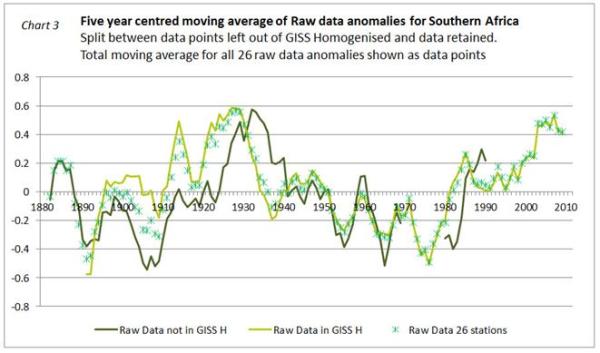

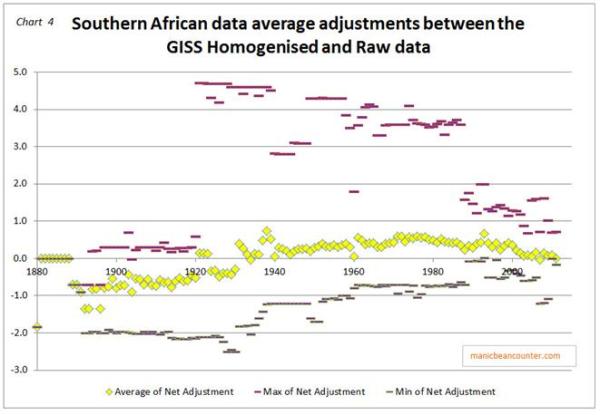

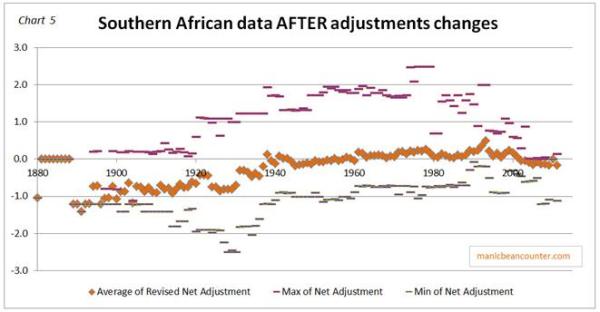

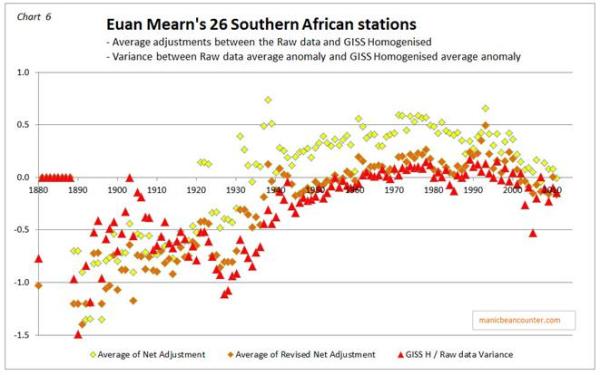

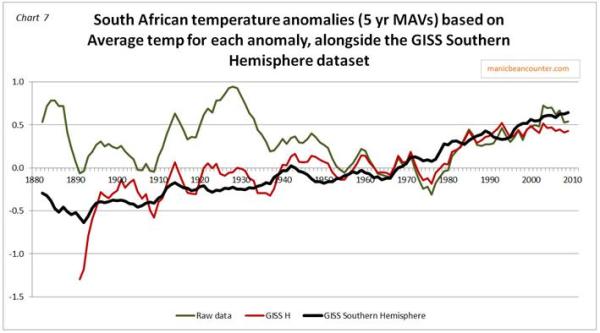

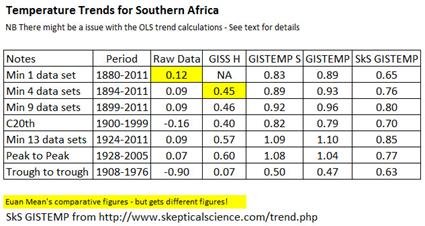

However, this definition of homogenisation appears to be different from that used by GHCN and NASA GISS. When Euan Mearns looked at temperature adjustments in the Southern Hemisphere and in the Arctic6, he found numerous examples in the GHCN and GISS homogenisations of infilling of some missing data and, to a greater extent, deleted huge chunks of temperature data. For example this graphic is Mearns’ spreadsheet of adjustments between GHCNv2 (raw data + adjustments) and the GHCNv3 (homogenised data) for 25 stations in Southern South America. The yellow cells are where V2 data exist V3 not; the greens cells V3 data exist where V2 data do not.

Definition of temperature homogenisation

A more general definition that encompasses the GHCN / GISS adjustments is of broadly making the data homogenous. It is not done by simply blending the data together and smoothing out the data. Homogenisation also adjusts anomalous data as a result of pairwise comparisons between local temperature stations, or in the case of extreme differences in the GHCN / GISS deletes the most anomalous data. This is a much looser and broader process than homogenisation of milk, or putting some food through a blender.

The definition I cover in more depth in the appendix.

The Consequences of Making Data Homogeneous

A consequence of cleansing the data in order to make it more homogenous gives a distinction that is missed by many. This is due to making the strong assumption that there are no climatic differences between the temperature stations in the homogenisation area.

Homogenisation is aimed at adjusting for the measurement biases to give a climatic reading for the location where the temperature station is located that is a closer approximation to what that reading would be without those biases. With the strong assumption, making the data homogenous is identical to removing the non-climatic inhomogeneities. Cleansed of these measurement biases the temperature data is then both the average temperature readings that would have been generated if the temperature station had been free of biases and a representative location for the area. This latter aspect is necessary to build up a global temperature anomaly, which is constructed through dividing the surface into a grid. Homogenisation, in the sense of making the data more homogenous by blending is an inappropriate term. All what is happening is adjusting for anomalies within the through comparisons with local temperature stations (the GHCN / GISS method) or comparisons with an expected regional average (the Berkeley Earth method).

But if the strong assumption does not hold, homogenisation will adjust these climate differences, and will to some extent fail to eliminate the measurement biases. Homogenisation is in fact made more necessary if movements in average temperatures are not the same and the spread of temperature data is spatially uneven. Then homogenisation needs to not only remove the anomalous data, but also make specific locations more representative of the surrounding area. This enables any imposed grid structure to create an estimated average for that area through averaging the homogenized temperature data sets within the grid area. As a consequence, the homogenised data for a temperature station will cease to be a closer approximation to what the thermometers would have read free of any measurement biases. As homogenisation is calculated by comparisons of temperature stations beyond those immediately adjacent, there will be, to some extent, influences of climatic changes beyond the local temperature stations. The consequences of climatic differences within the homogenisation area include the following.

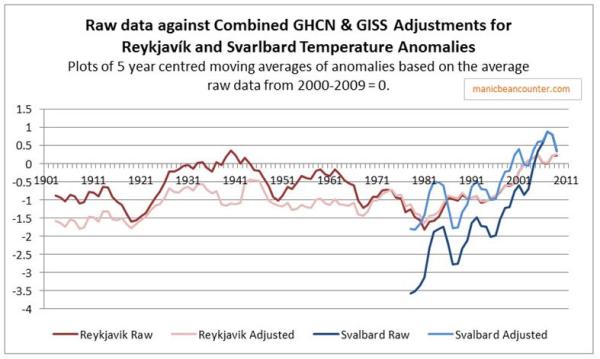

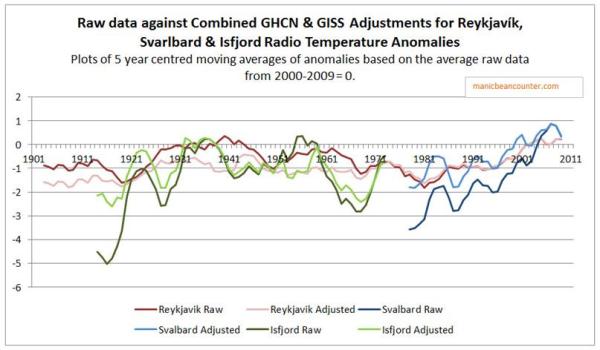

- The homogenised temperature data for a location could appear largely unrelated to the original data or to the data adjusted for known biases. This could explain the homogenised Reykjavik temperature, where Trausti Jonsson of the Icelandic Met Office, who had been working with the data for decades, could not understand the GHCN/GISS adjustments7.

- The greater the density of temperature stations in relation to the climatic variations, the less that climatic variations will impact on the homogenisations, and the greater will be the removal of actual measurement biases. Climate variations are unlikely to be much of an issue with the Western European and United States data. But on the vast majority of the earth’s surface, whether land or sea, coverage is much sparser.

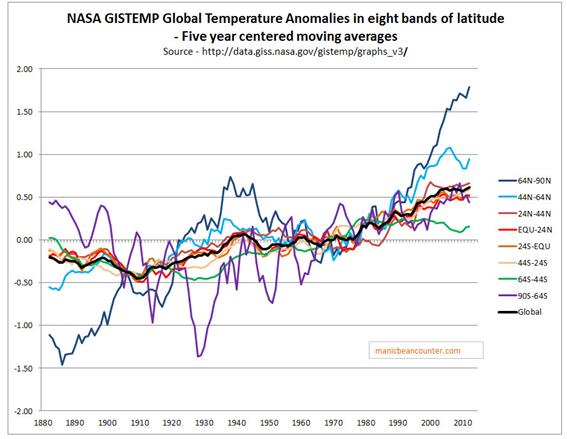

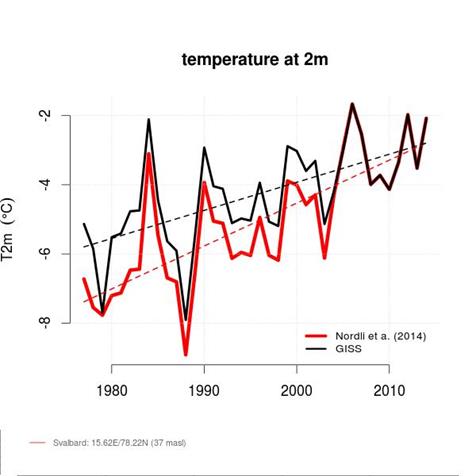

- If the climatic variation at a location is of different magnitude to that of other locations in the homogenisation area, but over the same time periods and direction, then the data trends will be largely retained. For instance, in Svarlbard the warming temperature trends of the early twentieth century and from the late 1970s were much greater than elsewhere, so were adjusted downwards8.

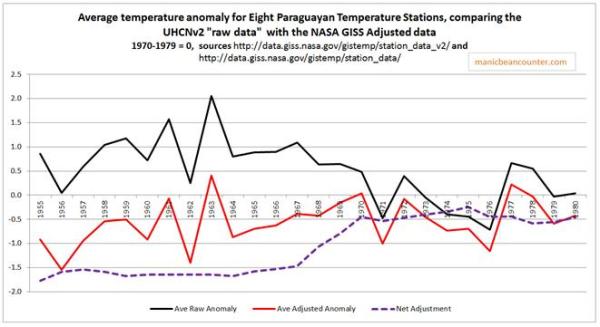

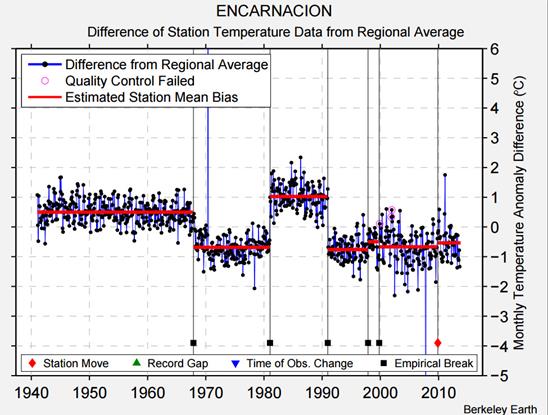

- If there are differences in the rate of temperature change, or the time periods for similar changes, then any “anomalous” data due to climatic differences at the location will be eliminated or severely adjusted, on the same basis as “anomalous” data due to measurement biases. For instance in large part of Paraguay at the end of the 1960s average temperatures by around 1oC. Due to this phenomena not occurring in the surrounding areas both the GHCN and Berkeley Earth homogenisation processes adjusted out this trend. As a consequence of this adjustment, a mid-twentieth century cooling in the area was effectively adjusted to out of the data9.

- If a large proportion of temperature stations in a particular area have consistent measurement biases, then homogenisation will retain those biases, as it will not appear anomalous within the data. For instance, much of the extreme warming post 1950 in South Korea is likely to have been as a result of urbanization10.

Other Comments

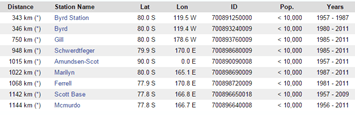

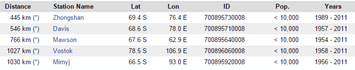

Homogenisation is just part of the process of adjusting data for the twin purposes of attempting to correct for biases and building a regional and global temperature anomalies. It cannot, for instance, correct for time of observation biases (TOBS). This needs to be done prior to homogenisation. Neither will homogenisation build a global temperature anomaly. Extrapolating from the limited data coverage is a further process, whether for fixed temperature stations on land or the ship measurements used to calculate the ocean surface temperature anomalies. This extrapolation has further difficulties. For instance, in a previous post11 I covered a potential issue with the Gistemp proxy data for Antarctica prior to permanent bases being established on the continent in the 1950s. Making the data homogenous is but the middle part of a wider process.

Homogenisation is a complex process. The Venema et al 20123 paper on the benchmarking of homogenisation algorithms demonstrates that different algorithms produce significantly different results. What is clear from the original posts on the subject by Paul Homewood and the more detailed studies by Euan Mearns and Roger Andrews at Energy Matters, is that the whole process of going from the raw monthly temperature readings to the final global land surface average trends has thrown up some peculiarities. In order to determine whether they are isolated instances that have near zero impact on the overall picture, or point to more systematic biases that result from the points made above, it is necessary to understand the data available in relation to the overall global picture. That will be the subject of my next post.

Kevin Marshall

Notes

- GUIDELINES ON CLIMATE METADATA AND HOMOGENIZATION by Enric Aguilar, Inge Auer, Manola Brunet, Thomas C. Peterson and Jon Wieringa

- Steven Mosher – Guest post : Skeptics demand adjustments 09.02.2015

- Venema et al 2012 – Venema, V. K. C., Mestre, O., Aguilar, E., Auer, I., Guijarro, J. A., Domonkos, P., Vertacnik, G., Szentimrey, T., Stepanek, P., Zahradnicek, P., Viarre, J., Müller-Westermeier, G., Lakatos, M., Williams, C. N., Menne, M. J., Lindau, R., Rasol, D., Rustemeier, E., Kolokythas, K., Marinova, T., Andresen, L., Acquaotta, F., Fratianni, S., Cheval, S., Klancar, M., Brunetti, M., Gruber, C., Prohom Duran, M., Likso, T., Esteban, P., and Brandsma, T.: Benchmarking homogenization algorithms for monthly data, Clim. Past, 8, 89-115, doi:10.5194/cp-8-89-2012, 2012.

- …and Then There’s Physics – Temperature homogenisation 01.02.2015

- See my post Temperature Homogenization at Puerto Casado 03.05.2015

-

For example

- See my post Reykjavik Temperature Adjustments – a comparison 23.02.2015

- See my post RealClimate’s Mis-directions on Arctic Temperatures 03.03.2015

- See my post Is there a Homogenisation Bias in Paraguay’s Temperature Data? 02.08.2015

- NOT A LOT OF PEOPLE KNOW THAT (Paul Homewood) – UHI In South Korea Ignored By GISS 14.02.2015

Appendix – Definition of Temperature Homogenisation

When discussing temperature homogenisations, nobody asks what the term actual means. In my house we consume homogenised milk. This is the same as the pasteurized milk I drank as a child except for one aspect. As a child I used to compete with my siblings to be the first to open a new pint bottle, as it had the cream on top. The milk now does not have this cream, as it is blended in, or homogenized, with the rest of the milk. Temperature homogenizations are different, involving changes to figures, along with (at least with the GHCN/GISS data) filling the gaps in some places and removing data in others1.

But rather than note the differences, it is better to consult an authoritative source. From Dictionary.com, the definitions of homogenize are:-

verb (used with object), homogenized, homogenizing.

- to form by blending unlike elements; make homogeneous.

- to prepare an emulsion, as by reducing the size of the fat globules in (milk or cream) in order to distribute them equally throughout.

-

to make uniform or similar, as in composition or function:

to homogenize school systems.

- Metallurgy. to subject (metal) to high temperature to ensure uniform diffusion of components.

Applying the dictionary definitions, data homogenization in science is not about blending various elements together, nor about additions or subtractions from the data set, or adjusting the data. This is particularly true in chemistry.

For UHCN and NASA GISS temperature data homogenization involves removing or adjusting elements in the data that are markedly dissimilar from the rest. It can also mean infilling data that was never measured. The verb homogenize does not fit the processes at work here. This has led to some, like Paul Homewood, to refer to the process as data tampering or worse. A better idea is to look further at the dictionary.

Again from Dictionary.com, the first two definitions of the adjective homogeneous are:-

- composed of parts or elements that are all of the same kind; not heterogeneous:

a homogeneous population.

- of the same kind or nature; essentially alike.

I would suggest that temperature homogenization is a loose term for describing the process of making the data more homogeneous. That is for smoothing out the data in some way. A false analogy is when I make a vegetable soup. After cooking I end up with a stock containing lumps of potato, carrot, leeks etc. I put it through the blender to get an even constituency. I end up with the same weight of soup before and after. A similar process of getting the same after homogenization as before is clearly not what is happening to temperatures. The aim of making the data homogenous is both to remove anomalous data and blend the data together.