Summary

Taking court action to compel Governments to enforce the Paris Climate Agreement is against the real spirit of that Agreement. Controlling global GHG emissions consistent with 2°C, or 1.5°C is only an aspiration, made unachievable by allowing developing countries to decide for themselves when to start reducing their emissions. In the foreseeable future, the aggregate impact of emissions reduction policies will fail to even reduce global emissions. Therefore, costly emissions reductions policies will always end up being net harmful to the countries where they are imposed. Governments wanting to both be players on the world stage and serve their countries give the appearance of taking action of controlling emissions, whilst in substance doing very little. This is the real spirit of the Paris Climate Agreement. To take court action to compel a change of policy action in the name of that Agreement should be struck off on that basis. I use activist group Plan B’s case before the British Court to get the British Government to make even deeper emissions cuts than those under the Climate Change Act 2008.

Plan B’s Case at the High court

Last week BBC’s environment analyst Roger Harrabin reported Court action to save young from climate bill.

The campaigners – known collectively as Plan B – argue that if the UK postpones emissions cuts, the next generation will be left to pick up the bill.

It is seeking permission from a judge to launch formal legal action.

The government has promised to review its climate commitments.

A spokesperson said it was committed to tackling emissions.

But Plan B believes ministers may breach the law if they don’t cut emissions deeper – in line with an international agreement made in Paris at the end of 2015 to restrict global temperature rise to as close to 1.5C as possible.

From an obscure website crowdjustice

Plan B claim that the government is discriminating against the young by failing to cut emissions fast enough. During the hearing, they argued that the UK government’s current target of limiting global temperature rises to 2°C was not ambitious enough, and that the target ought to be lowered to 1.5°C, in line with the Paris Agreement that the UK ratified in 2015. Justice Supperstone postponed the decision until a later date.

Plan B on their own website state

Plan B is supporting the growing global movement of climate litigation, holding governments and corporations to account for climate harms, fighting for the future for all people, all animals and all life on earth.

What is the basis of discrimination?

The widely-accepted hypothesis is that unless global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions are reduced to near zero in little more than a generation, global average temperature rise will rise more than 2°C above pre-industrial levels. A further hypothesis is that this in turn will cause catastrophic climate change. Consequent on both hypotheses being true gives the case for policy action. Therefore, failure to reduce global GHG emissions will imperil the young.

A further conjecture is that if all signatories to the Paris Agreement fulfil their commitments it is sufficient to prevent 1.5°C or 2°C of warming. There are a number of documents to consider.

First is the INDC submissions (i.e. Nation States communications of their intended nationally determined contributions), collected together at the UNFCCC website. Most are in English. To find a country submission I suggest clicking on the relevant letter of the alphabet.

Second, to prevent my readers being send on a wild goose chase through small country submissions, some perspective is needed on relative magnitude of emissions. A clear secondary source (but only based on CO2 emissions) BP Data Analysis Global CO2 Emissions 1965-2017. More data on GHG emissions are from the EU Commissions EDGAR Emissions data and the World Resources Institute CAIT Climate Data Explorer.

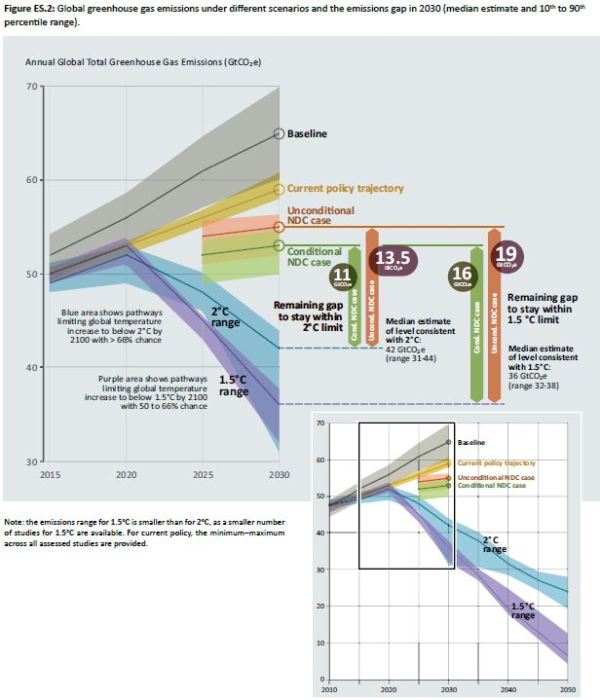

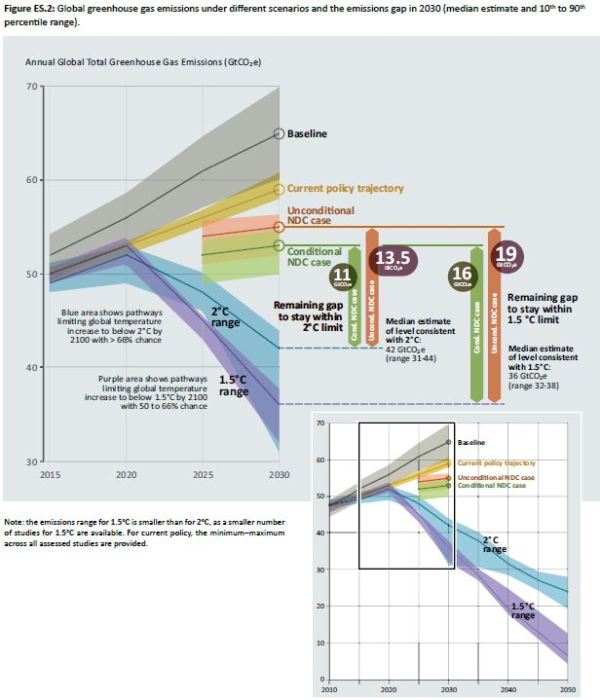

Third is the empirical scale of the policy issue. The UNEP emissions Gap Report 2017 (pdf), published in October last year is the latest attempt to estimate the scale of the policy issue. The key is the diagram reproduced below.

The total of all commitments will still see aggregate emissions rising into the future. That is, the aggregate impact of all the nationally determined contributions is to see emissions rising well into the future. So the response it to somehow persuade Nations States to change their vague commitments to such an extent that aggregate emissions pathways sufficient to prevent 1.5°C or 2°C of warming?

The relevant way to do this ought to be through the Paris Agreement.

Fourth is the Adoption Paris Agreement itself, as held on the UNFCCC website (pdf).

Paris Agreement key points

I would draw readers to Article 2.1(a)

- Holding the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels and pursuing efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels, recognizing that this would significantly reduce the risks and impacts of climate change;

Article 2.2

- This Agreement will be implemented to reflect equity and the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities, in the light of different national circumstances.

My interpretation is that the cumulative aggregate reduction will be only achieved by if those countries that (in the light of their national circumstances) fail to follow the aggregate pathways, are offset by other countries cutting their emissions by a greater amount. It is a numbers game. It is not just a case of compelling some countries to meet the 1.5°C pathway but to compel them to exceed it by some margin.

I would also draw readers to Article 4.1

In order to achieve the long-term temperature goal set out in Article 2, Parties aim to reach global peaking of greenhouse gas emissions as soon as possible, recognizing that peaking will take longer for developing country Parties, and to undertake rapid reductions thereafter in accordance with best available science, so as to achieve a balance between anthropogenic emissions by sources and removals by sinks of greenhouse gases in the second half of this century, on the basis of equity, and in the context of sustainable development and efforts to eradicate poverty.

My reading is that any country defined as “developing” has only an aim of reducing emissions after peaking of their emissions. When they choose to do so depends on a number of criteria. There is not clear mechanism for deciding this, and no surrender of decision-making by countries to external bodies.

Implications of the Paris Agreement

Many developing countries emissions are increasing their emissions. They agreement does not compel them to change course in the near future. Empirically that means to achieve the goals the aggregate emission reductions of countries reducing their emissions must be such that they cancel out the emissions increases in the developing countries. Using EDGAR figures for GHG emissions, and the Rio Declaration 1992 for developing countries (called Non-Annex countries) I estimate they accounted for 64% of global GHG emissions in 2012, the latest year available.

All other sources sum to 19 GtCO2e, the same as the emissions gap between the unconditional INDC case and the 1.5°C case. This presents a stark picture. Even if emissions from all other sources are eliminated by 2030, AND the developing countries do not increase their emissions to 2030, cumulative global emissions are very likely to exceed the 1.5°C and the 2°C warming targets unless the developing countries reduce their emissions rapidly after 2030. That is close down fairly new fossil fuel power stations; remove from the road millions of cars, lorries and buses; and reduce the aspirations of the emerging middle classes to improving life styles. The reality is quite the opposite. No new policies are on the horizon that would significantly reduce global GHG emissions, either from the developed countries in the next couple of years, or the developing countries to start in just over a decade from now. Reading the comments in the INDC emissions (e.g. Indonesia, Pakistan, India), a major reason is that these governments are not willing to sacrifice the futures of their young through risking economic growth and political stability to cut their emissions. So rather than Plan B take the UK Government to a UK Court, they should be persuading those Governments who do not share their views (most of them) of the greater importance of their case. After all, unlike proper pollution (such as smoke), it does not matter where the emissions are generated in relation to the people affected.

It gets worse. It could be argued that the countries that most affected by mitigation policies are not the poorest seeing economic growth and political stability smashed. It is the fossil fuel dependent countries. McGlade and Ekins 2015 (The geographical distribution of fossil fuels unused when limiting global warming to 2°C) estimated, said to achieve even 2°C target 75% of proven reserves and 100% of new discoveries must be left in the ground. Using these global estimates and the BP estimated proven reserves of fossil fuels I created the following apportionment by major countries.

The United States has the greatest proven fossil fuel reserves in terms of potential emissions. But if one looks at fossil fuel revenues relative to GDP, it is well down the league table. To achieve emission targets countries such like Russia, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Turkmenistan, Iraq, and Iran must all be persuaded to shut down their down sales of fossil fuels long before the reserves are exhausted, or markets from developing countries dry up. To do this in a generation would decimate their economies. However, given the increase in fossil fuel usage from developing countries, and the failure of developed countries to significantly reduce emissions through policy this hardly seems a large risk.

However, this misses the point. The spirit of the Paris Agreement is not to cut emissions, but to be seen to be doing something about climate change. For instance, China were held up by the likes of President Obama for aiming to both top out its emissions by 2030, and reduce emissions per unit of GDP. The USA and the EU did this decades ago, so China’s commitments are little more than a Business-as-usual scenario. Many other countries emissions reduction “targets” are attainable without much actual policy. For example, Brazil’s commitment is to “reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 43% below 2005 levels in 2030.” It sounds impressive, until one reads this comment under “Fairness and Ambition”

Brazil’s current actions in the global effort against climate change represent one of the largest undertakings by any single country to date, having reduced its emissions by 41% (GWP-100; IPCC SAR) in 2012 in relation to 2005 levels.

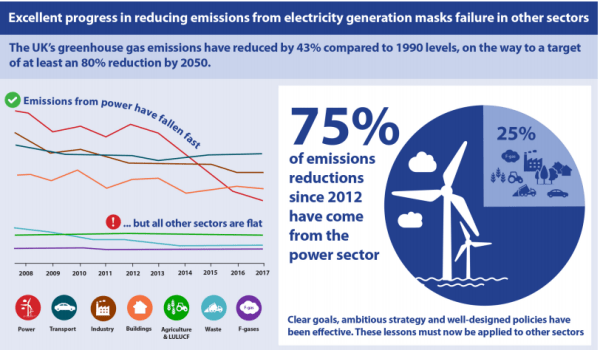

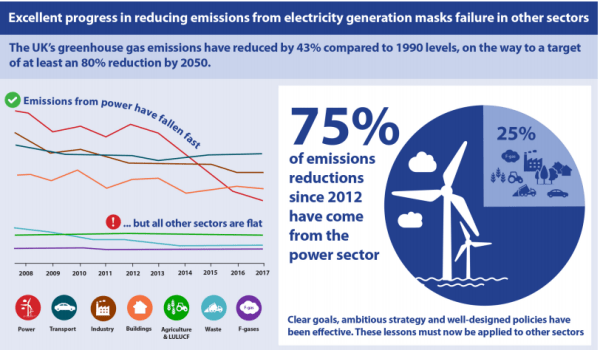

Brazil intends to reduce emissions by a further 2% compared to 2005 levels. Very few targets are more than soft targets relative to current or projected trends. Yet the outcome of COP21 Paris enabled headlines throughout the world to proclaim a deal had been reached “to limit global warming to “well below” 2C, aiming for 1.5C”. It enables most Governments to juggle being key players on a world stage, have alarmists congratulating them on doing their bit on saving the planet, whilst making sure that serving the real needs of their countries is not greatly impeded. It is mostly win-win as long as countries do not really believe that targets are achievable. This is where Britain has failed. Under Tony Blair, when the fever of climate alarmism at its height, backed up by the political spin of New Labour and a Conservative opposition wanting to ditch its unelectable image, Green activists wrote the Climate Change Act 2008 with the strict targets to be passed. Britain swallowed climate alarmism whole, and now as a country that keep its promises is implementing useless and costly policies. But they have kept some form of moderation in policies until now. This is illustrated by a graphic from a Committee on Climate Change report last week “Reducing UK emissions 2018 – Progress Report to Parliament” (pdf) (and referenced at cliscep)

Whilst emissions have come down in the power sector they are flat in transport, industry and in buildings. Pushing real and deep reductions in these sectors means for young people pushing up the costs of motoring (placing driving a car out of the reach of many), of industry (raising costs relative to the countries – especially the non-policy developing countries) and buildings in a country where planning laws make home-owning unaffordable for many and where costs of renting is very high. This on top of further savings in the power industry will be ever more costly as the law of diminishing returns sets in. Forcing more urgent policy actions will increase the financial and other burdens on the young people of today, but do virtually nothing to reach the climate aspirations of the Paris Agreement due to Britain now having less than 1% of global emissions. The Government could be forced out of political fudging to impose policies that will be net harmful to the young and future generations.

Plan B are using an extreme activist interpretation. As reported in Climate Home News after the postponement.

“The UK is not doing enough,” Tim Crosland, director of Plan B told Climate Home News. “The benchmark target is now out of place. We are arguing that it is a breach of human rights.”

The UK has committed to cut emissions by at least 80% of 1990 levels by 2050, with an aim to limit global temperature rise to 2C.

Under the 2008 Climate Change Act, the secretary can revise the target to reflect significant developments in climate change science or in international law or policy.

Plan B want to see the target lowered to be in line with 1.5C, the lower target of the Paris Agreement, which the UK ratified in 2016.

As stated, insofar as the Paris Climate Agreement is a major development of policy, it is one of appearing to do a lot whilst doing very little. By these terms, the stronger case is for repealing the Act, not strengthening its clauses.

But what if I am wrong on this Paris Agreement being just an exercise in appearances? This then it should be recognized that developing countries will only start to reduce their emissions at some time in the future. By implication, for the world to meet the 1.5°C warming limit, developing countries should be pursuing and emissions reduction pathway much steeper than the 25% reduction between 2015 and 2030 implied in the Emissions GAP Report graphic. It should be at least 50% and nearer 100% in the next decade. Given that the Climate Change Act was brought in so that Britain could lead the world on climate change, Plan B should be looking for a 100% reduction by the end of the year.

Kevin Marshall

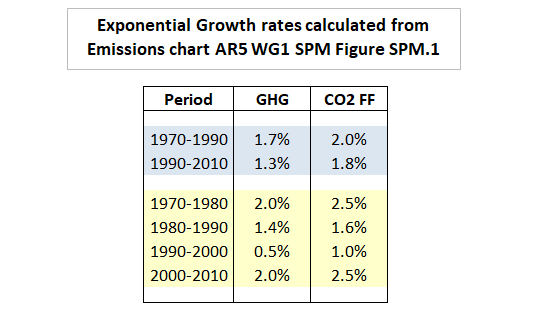

Figure 2 : AR5 WG3 SPM.1 Total annual anthropogenic GHG emissions (GtCO2eq/yr) by groups of gases 1970-2010. FOLU is Forestry and Other Land Use.

Figure 2 : AR5 WG3 SPM.1 Total annual anthropogenic GHG emissions (GtCO2eq/yr) by groups of gases 1970-2010. FOLU is Forestry and Other Land Use.