I believe that there is a prayer that politicians should adopt.

Called the Serenity Prayer, and written by Reinhold Niebuhr it begins

God grant me the serenity

to accept the things I cannot change;

courage to change the things I can;

and wisdom to know the difference.

The order is the right way round. Most “things” a politician – or even a ruling political party – cannot change. It is in the identification of the things that they can change for the better where they can make a positive difference.

An example comes from the end of last month. For a few days the news in Britain was dominated for days with the stories of the greatest ever wildfire in California. Called the Camp Fire, it killed 86, destroyed 19,000 homes and burnt 240 square miles (62,000 ha)

CBS News 60 Minutes has this short report.

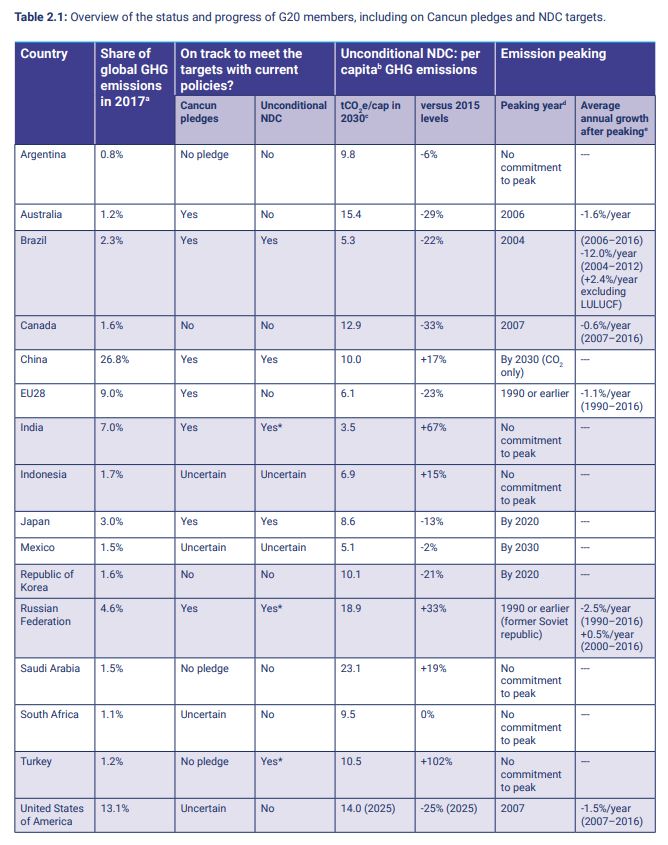

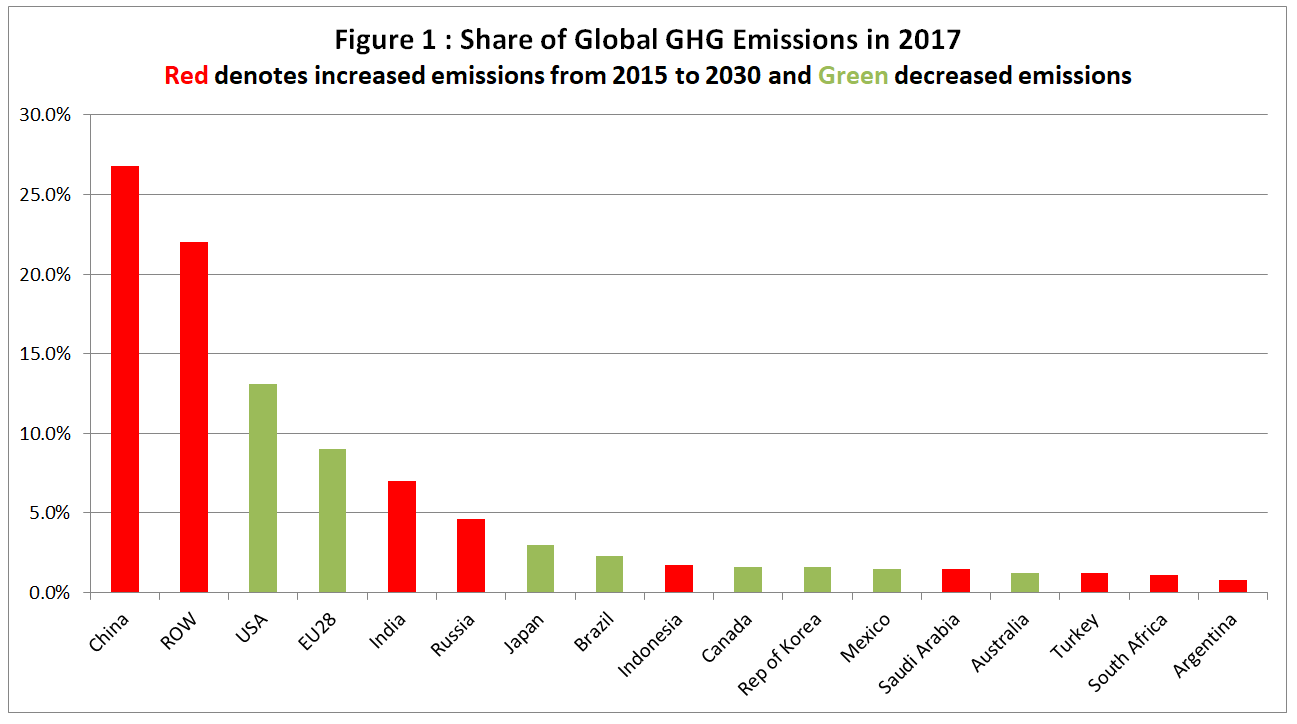

Many politicians, including Governor Brown, blamed climate change. Yet even if wildfires were solely from that cause, the ultimate cause is supposed to be from global greenhouse gas emissions. As in 2016 California’s emissions were around 430 MtCO2e – or about 0.8% of the global total – any climate change policies will make virtually zero difference to global emissions. Even under the 2015 proposed contribution from the USA would not have made much difference as most of the forecast drop in emissions was due to non-policy trends, not due to actual policies. Policy that achieves much less than 10% real reduction from a country that has one-eighth of global emissions is hardly going to have an impact in a period when net global emissions are increasing. That is, impact of any mitigation policies by the State of California or the United States will have approximately zero impact on global emissions.

But no reasonable person would claim that it was all down to climate change, just that climate change may have made the risk of wild fires a little greater.

What are the more immediate causes of wild fires? This is what Munich Re has to say on wildfires in Southeast Australia. (Bold mine)

The majority of bushfires in southeast Australia are caused by human activity

Bushfire is the only natural hazard in which humans have a direct influence on the hazard situation. The majority of bushfires near populated areas are the consequence of human activity. Lightning causes the smaller portion naturally. Sometimes, a carelessly discarded cigarette or a glass shard, which can focus the sun’s rays is all it takes to start a fire. Heat from motors or engines, or electric sparks from power lines and machines can ignite dry grass. Besides this accidental causes, a significant share of wildfires are started deliberately.

Humans also change the natural fire frequency and intensity. They decrease the natural fire frequency due to deliberate fire suppression near populated areas. If there is no fuel-reduction burning in forests for the purposes of fire prevention, large quantities of combustible material can accumulate at ground level.

Surface fires in these areas can become so intense due to the large amounts of fuel that they spread to the crowns of the trees and rapidly grow into a major fire. If humans had not intervened in the natural bushfire regime, more frequent low-intensity fires would have consumed the forest undergrowth and ensured that woodland grasses and scrubs do not proliferate excessively.

David Evans expands on the issue of fuel load in a 2013 article.

The immediate cause of wildfires is human. Near to people’s homes or businesses there is little that can be done to prevent fires either accidental or deliberate.

But, as any fire safety course will explain, for a fire to happen requires heat, fuel and oxygen. A few tenths of a degree of warming is not going to increase the heat source significantly. As Munich Re explains successful suppression of small fires, or forest management that allows dead material to accumulate, or does not thin the forest. or create fire-breaks will increase the continuous and rich fuel for fires to spread. That is, the unintended consequence of certain types of forest management will be to increase risk of severe fires.

President Trump was then correct in blaming poor forest management for the horrific fire. The reaction from firefighters that the tweets were “demeaning” and “ill-informed” were misplaced. If bad policy contributed to the severity of a fire then politicians should share some of the blame for the damage caused. They should not be defended by those risking their lives to limit the damage resulting from bad policies. If poor building regulations lead to many deaths in a large building then those responsible for the regulations would shoulder some of the blame for those deaths even if an arsonist started the fire. The same applies to forests. After major disasters such as air crashes and earthquakes, regulations are often put in place to prevent future similar disasters even when such regulations would not have prevented the actual disaster. The result of a disaster is to concentrate minds on the wider aspects and plug gaps. But like major disasters, if regulations contributed to the extent of the disaster, the aftermath will be to shift blame elsewhere then fix the underlying problem in a raft of – mostly unnecessary – regulations. President Trump broke these unwritten political rules. But the results are the same, and have occurred quite quickly.

When Trump visited the site of the Camp Fire he met with outgoing Governor Jerry Brown and Lt. Gov. Gavin Newsom he stated on November 19th

Is it happening? Things are changing. ….. And I think, most importantly, we’re doing things about. We’re going to make it better. We’re going to make it a lot better. And it’s going to happen as quickly as it can possibly happen.

From the Daily Caller and WUWT, on December 23rd President Trump signed into law new wildfire legislation that will better allow such fire-prevention management policies. On Christmas Eve President Trump followed this up with an executive order allowing agencies to do more to prevent massive wildfires.

Returning to the serenity prayer, in issuing an Executive order to allow government agencies to reduce fire risk President Trump has done something that is within his power. GOP legislation to better enable others to carry out similar forest management policies, has a slightly less direct impact. Democrats whinging about climate change is far more than failing to accept the things they cannot change. It is about blocking actions that can limit risk and extent of wild fires to maintain ineffectual and costly policies.