Last week, Wattupwiththat post “Climate Study: British Children Won’t Know What Milk Tastes Like”. Whilst I greatly admire Anthony Watts, I think this title entirely misses the point.

It refers to an article at the Conservation “How climate change will affect dairy cows and milk production in the UK – new study” by two authors at Aberystwyth University, West Wales. This in turn is a write up of a Plos One article published in May “Spatially explicit estimation of heat stress-related impacts of climate change on the milk production of dairy cows in the United Kingdom“. The reason I disagree is that even with very restrictive assumptions, this paper shows that even with large changes in temperature, the unmitigated costs of climate change are very small. The authors actually give some financial figures. Referring to the 2190s the PLOS One abstract ends:-

In the absence of mitigation measures, estimated heat stress-related annual income loss for this region by the end of this century may reach £13.4M in average years and £33.8M in extreme years.

The introduction states

The value of UK milk production is around £4.6 billion per year, approximately 18% of gross agricultural economic output.

For the UK on average Annual Milk Loss (AML) due to heat stress is projected to rise from 40 kg/cow to over 170 kg/cow. Based on current yields it is from 0.5% to 1.8% in average years. The most extreme region is the south-east where average AML is projected to rise from 80 kg/cow to over 320 kg/cow. That is from 1% to 4.2% in average years. That is, if UK dairy farmers totally ignore the issue of heat stress for decades the industry could see average revenue losses from heat stress rise on average from £23m to £85m. The financial losses are based on constant prices of £0.30 per litre.

With modeled estimates over very long periods, it is worth checking the assumptions.

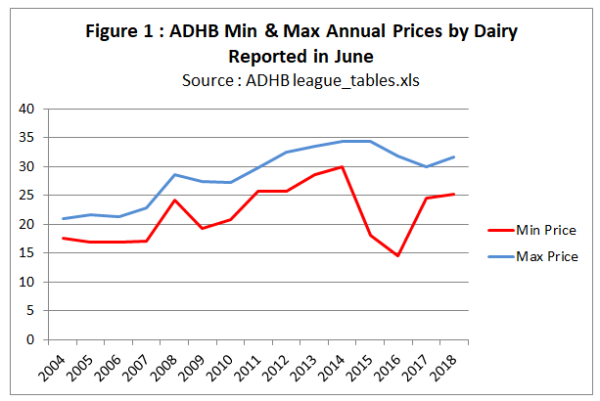

Price per liter of milk

The profits are based upon a constant price of £0.30 a liter. But prices can fluctuate according to market conditions. Data on annual average prices paid is available from AHDB Dairy, ” a levy-funded, not-for-profit organisation working on behalf of Britain’s dairy farmers.” Each month, since 2004, there are reported the annual average prices paid by dairies over a certain size available here. That is 35-55 in any one month. I have taken the minimum and maximum prices for reported in June each year and shown in Figure 1.

Even annual average milk prices fluctuate depending on market conditions. If milk production is reduced in summer months due to an unusual heat wave causing heat stress, ceteris paribus, prices will rise. It could be that a short-term reduction in supply would increase average farming profits if prices are not fixed. It is certainly not valid to assume fixed prices over many decades.

Dumb farmers

From the section in the paper “Milk loss estimation methods”

It was assumed that temperature and relative humidity were the same for all systems, and that no mitigation practices were implemented. We also assumed that cattle were not significantly different from the current UK breed types, even though breeding for heat stress tolerance is one of the proposed measures to mitigate effects of climate change on dairy farms.

This paper is looking at over 70 years in the future. If heatwaves were increasing, so yields falling and cattle were suffering, is it valid to assume that farmers will ignore the problem? Would they not learn from areas with more extreme heatwaves in summer elsewhere such as in central Europe? After all in the last 70 years (since the late 1940s) breeding has increased milk yields phenomenally (from AHDB data, milk yields per cow have increased 15% from 2001/2 to 2016/7 alone) so a bit of breeding to cope with heatwaves should be a minor issue.

The Conversation article states the implausible assumptions in a concluding point.

These predictions assume that nothing is done to mitigate the problems of heat stress. But there are many parts of the world that are already much hotter than the UK where milk is produced, and much is known about what can be done to protect the welfare of the animals and minimise economic losses from heat stress. These range from simple adaptations, such as the providing shade, to installing fans and water misting systems.

Cattle breeding for increased heat tolerance is another potential, which could be beneficial for maintaining pasture-based systems. In addition, changing the location of farming operations is another practice used to address economic challenges worldwide.

What is not recognized here is that farmers in a competitive market have to adapt in the light of new information to stay in business. That is the authors are telling farmers what they will be fully aware of to the extent that their farms conform to the average. Effectively assuming people and dumb, then telling them obvious, is hardly going to get those people to take on board one’s viewpoints.

Certainty of global warming

The Conversation article states

Using 11 different climate projection models, and 18 different milk production models, we estimated potential milk loss from UK dairy cows as climate conditions change during the 21st century. Given this information, our final climate projection analysis suggests that average ambient temperatures in the UK will increase by up to about 3.5℃ by the end of the century.

This warming is consistent with the IPCC global average warming projections using RCP8.5 non-mitigation policy scenario. There are two alternative, indeed opposite, perspectives that might lead rational decision-makers to think this quantity of warming is less than certain.

First, the mainstream media, where the message being put out is that the Paris Climate Agreement can constrain global warming to 2°C or 1.5°C above the levels of the mid-nineteenth century. With around 1°C of warming already if it is still possible to constrain additional global warming to 0.5°C, why should one assume that 3.5°C of warming for the UK is more than a remote possibility in planning?

Second, one could look at the track record of global warming projections from the climate models. The real global warming scare kicked-off with James Hansen’s testimony to Congress in 1988. Despite actual greenhouse gas emissions being closely aligned with rapid warming, actual global warming has been most closely aligned with the assumption of the impact of GHG emissions being eliminated by 2000. Now, if farming decision-makers want to still believe that emissions are the major driver of global warming, they can find plenty of excuses for the failure linked from here. But, rational decision-makers tend to look at the track record and thus take consistent decision-makers with more than a pinch of salt.

Planning horizons

The Conversation article concludes

(W)e estimate that by 2100, heat stress-related annual income losses of average size dairy farms in the most affected regions may vary between £2,000-£6,000 and £6,000-£14,000 (in today’s value), in average and extreme years respectively. Armed with these figures, farmers need to begin planning for a hotter UK using cheaper, longer-term options such as planting trees or installing shaded areas.

This compares to the current the UK average annual dairy farm business income of £80,000 according to the PLOS One article.

There are two sides to investment decision-making. There are potential benefits – in this case avoidance of profit loss – netted against the potential benefits. ADHB Dairy gives some figures for the average herd size in the UK. In 2017 it averaged 146 cows, almost double the 75 cows in 1996. In South East England, that is potentially £41-£96 a cow, if the average herd size there is same as the UK average. If the costs rose in a linear fashion, that would be around 50p to just over a pound a year per cow in the most extreme affected region. But the PLOS One article states that costs will rise exponentially. That means there will be no business justification for evening considering heat stress for the next few decades.

For that investment to be worthwhile, it would require the annual cost of mitigating heat stress to be less than these amounts. Most crucially, rational decision-makers apply some sort of NPV calculation to investments. This includes a discount rate. If most of the costs are to be incurred decades from now – beyond the working lives of the current generation of farmers – then there is no rational reason to take into account heat stress even if global warming is certain.

Summary

The Paper Spatially explicit estimation of heat stress-related impacts of climate change on the milk production of dairy cows in the United Kingdom makes a number of assumptions to reach its headline conclusion of decreased milk yields due to heat stress by the end of the century. The assumption of constant prices defies the economic reality that prices fluctuate with changing supply. The assumption of dumb farmers defies the reality of a competitive market, where they have to respond to new information to stay in business. The assumption of 3.5°C warming in the UK can be taken as unlikely from either the belief Paris Climate Agreement with constrain further warming to 1°C or less OR that the inability of past climate projections to conform to the pattern of warming should give more than reasonable doubt that current projections are credible. Further the authors seem to be unaware of the planning horizons of normal businesses. Where there will be no significant costs for decades, applying any sort of discount rate to potential investments will mean instant dismissal of any consideration of heat stress issues at the end of the century by the current generation of farmers.

Taking all these assumptions together makes one realize that it is quite dangerous for specialists in another field to take the long range projections of climate models and apply to their own areas, without also considering the economic and business realities.

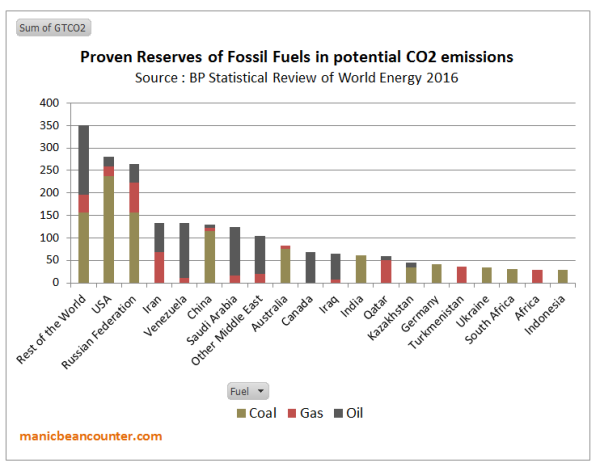

Figure 2 : AR5 WG3 SPM.1 Total annual anthropogenic GHG emissions (GtCO2eq/yr) by groups of gases 1970-2010. FOLU is Forestry and Other Land Use.

Figure 2 : AR5 WG3 SPM.1 Total annual anthropogenic GHG emissions (GtCO2eq/yr) by groups of gases 1970-2010. FOLU is Forestry and Other Land Use.