There is a huge build-up underway for the COP21 climate conference to be staged in Paris in November. Many countries and NGOs are pushing for an agreement that will constrain warming to just 2oC, but there are no publicly available figures of what this means for all the countries of the world. This is the gap I seek close with a series of posts. The first post is concerned with getting a perspective on global emissions and the UNIPCC targets.

In what follows, all the actual figures are obtained from three primary sources.

- Emissions data comes from the Carbon Dioxide Information Analysis Centre or CDIAC.

- Population data comes from the World Bank, though a few countries are missing. These are mostly from Wikipedia.

- The Emissions targets can be found in the Presentation for the UNIPCC AR5 Synthesis Report.

All categorizations and forecast estimates are my own.

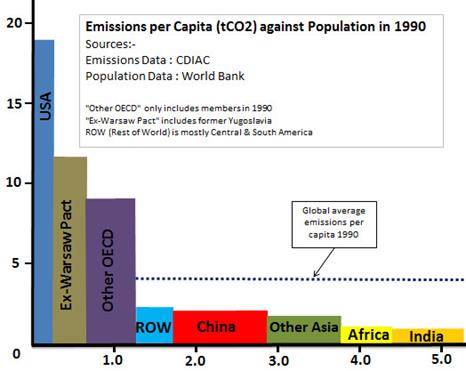

The 1990 Emissions Position

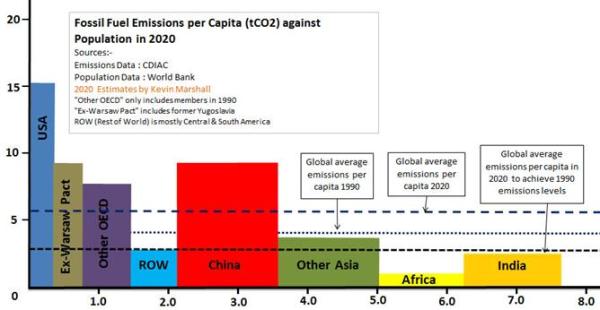

A starting point for emissions reductions is to stabilize emissions to 1990 levels, around the time that climate mitigation was first proposed. To illustrate the composition emissions I have divided the countries of the world into the major groups meaningful at that time – roughly into First World developed nations, the Second World developed communist countries and the Third World developing economies. The First World is represented by the OECD. I have only included members in 1990, with the USA split off. The Second World is the Ex-Warsaw pact countries, with the countries of the former Yugoslavia included as well. The rest are of the world is divided into five groups. I have charted the emissions per capita against the populations of these groups to come up with the following graph.

In rough terms, one quarter of the global population accounted for two-thirds of global emissions. A major reduction on total emissions could therefore be achieved by these rich countries taking on the burden of emissions reductions, and the other countries not increasing their emissions, or keeping growth to a minimum.

The 2020 emissions forecast

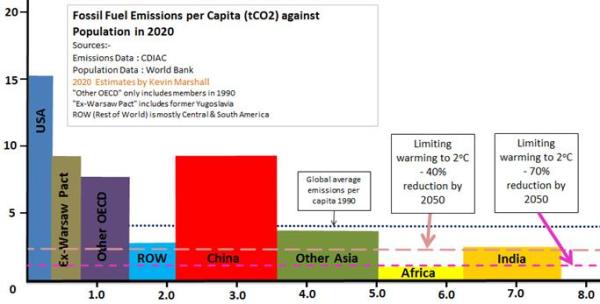

I have created a forecast of both emissions and population for 2020 using the data up to 2013 for both emissions and population. Mostly these are assuming the same change in the next seven years as the last. For emissions in the rapidly-growing countries this might be an understatement. For China and India I have done separate forecasts based on their emissions commitments. This gives the following graph.

The picture has changed dramatically. Population has increased by 2.4 billion or 45% and emissions by over 80%. Global average emissions per capita have increased from 4.1 to 5.2t/CO2 per capita. Due to the population increase, to return global emissions to 1990 levels would mean reducing average emissions per capita to 2.85t/CO2.

The composition of emissions has been even more dramatic. The former First and Second World countries will see a slight fall in emissions from 14.9 to 14.0 billion tonnes of CO2 and the global share will have reduced from 68% to 36%. Although total population will have increased on 1990, the slower growth than elsewhere means the share of global population has shrunk to just 19%. China will have a similar population and with forecast emissions of 13.1 billion tonnes of CO2, 33% of the global total.

The picture is not yet complete. On slide 30 of their Synthesis Report presentation the UNIPCC state

Measures exist to achieve the substantial emissions reductions required to limit likely warming to 2oC (40-70% emissions reduction in GHGs globally by 2050 and near zero GHGs in 2100)

The baseline is 2011, when global emissions were 29.74 billion t/CO2. In 2050 global population will be nearly nine billion. This gives an upper limit of 2.2 t/CO2 per capita and lower limit of 1.1 t/CO2 per capita.

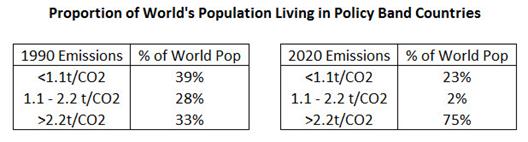

To put this in another perspective, consider the proportions of people living in countries that need emissions targets based on greater than 2.2t/CO2 emissions per capita.

In 1990, it was just a third of the global population. In 2020 it will be three quarters. No longer can an agreement on constraining global CO2 emissions be limited to a few countries. It needs to be truly global. The only area that meets the target is Africa, but even here the countries of Algeria, Egypt, Libya, Tunisia and South Africa would need to have emission reduction targets.

Further Questions

- What permutations are possible if other moral considerations are taken into account, like the developed countries bear the burden of emission cuts?

- What targets should be set for non-fossil fuel emissions, such as from Agriculture? Are these easier or harder to achieve than for fossil fuels?

- What does meeting emission targets mean for different types of economies? For instance are emission reductions more burdensome for the fast-growing emerging economies that for the developed economies?

- What are the measures that IPCC claims exist to reduce emissions? Are they more onerous than the consequences of climate change?

- Are there in place measures to support the states dependent on the production of fossil fuels? In particular, the loss of income to the Gulf States from leaving oil in the ground may further destabilize the area.

- What sanctions if some countries refuse to sign up to an agreement, or are politically unable to implement an agreement?

- What penalties will be imposed if countries fail to abide by the agreements made?

Kevin Marshall