The first stage of the 1997 Kyoto Protocol officially comes to an end today. We should say DNR – Do Not Resuscitate

The underpinnings of the Kyoto Protocol used benefit-cost analysis to achieve a compromise solution. To achieve is goal it needed ALL of the following assumptions to be true.

- CO2 causing a massive increase in global warming.

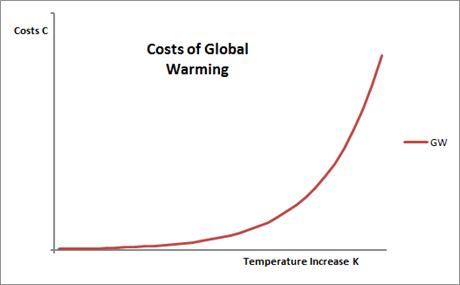

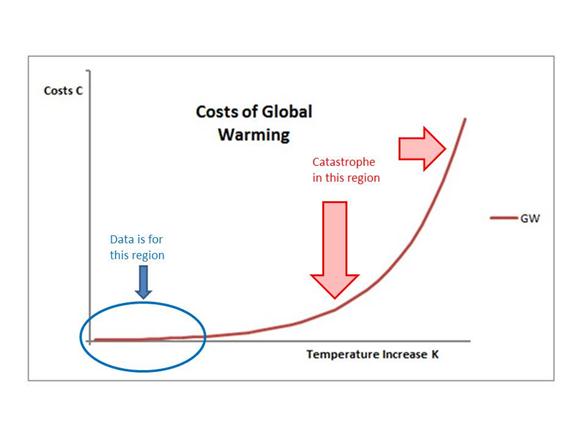

- For that warming to have massive catastrophic consequences.

- For economic theory to provide a theoretical solution with benefits ≥ costs.

- The actual solution matches the theory.

- There are no unintended consequences of actual policy implementation need to be taken into account.

- That the Kyoto Protocol was originally estimated at being 97% useless in constraining temperature rises.

CO2 causing a massive increase in warming.

If you still believe the hype that CO2 is going to cause a massive increase in global warming, you are now at odds with the latest estimates from the IPCC. David M. Hoffer at Wattsupwiththat shows why.

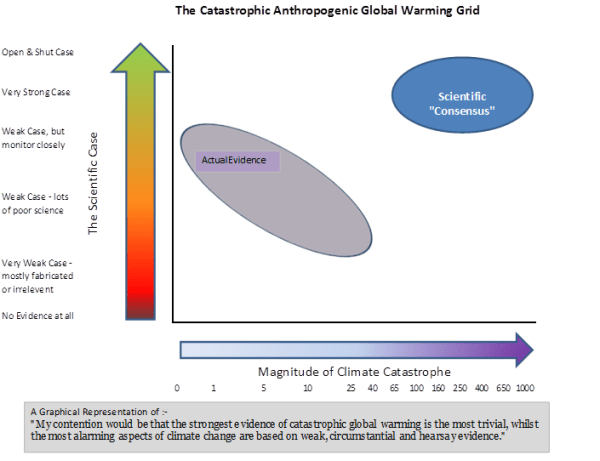

Massive catastrophic consequences

Where is the evidence of accelerating sea level rise; increasing tropical storms; desertification; accelerating rate of polar ice melt; disappearing Himalayan glaciers causing water shortages; or massively reduced crop yields in Africa leading to famines? Where is all the talk of reaching climate “tipping points”, which must be avoided at all costs? You will not find them in the latest AR5 SPM, because there is no half-decent scientific evidence to support these claims,

Support from economic theory?

William Nordhaus, the world’s leading climate change economist, calculates that the benefit-cost ratio is 1/7. Nordhaus accepts the first two points, but still calculates that on economic terms you should not touch the scheme with a bargepole. More recently, Dieter Helm has described emissions trading schemes as the most expensive way of reducing emissions. Both advocate a carbon tax.

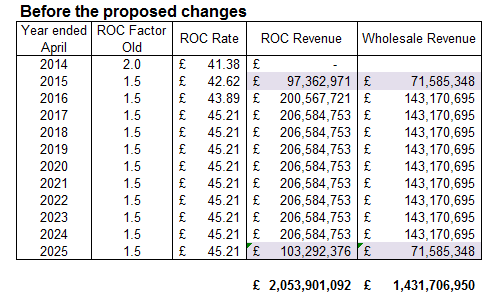

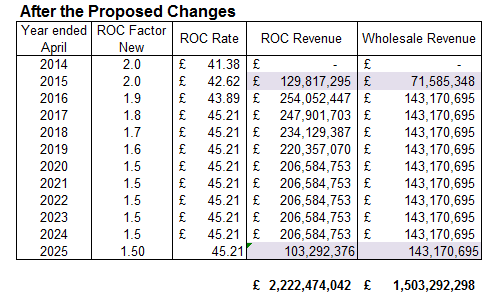

Actual scheme matches theory

Kyoto proposed that countries adopt an emissions trading scheme. In the EU it did not work because credits were issued at too low a cost.

Unintended Consequences

The emissions trading schemes have essentially collapsed, mostly because there has been no commitment to extend Kyoto. Given that there have been numerous fraud scandals from the large through to the small, this is no bad thing. The schemes are open to abuse, yet the investment banks that run them make billions of dollars annually.

Kyoto is Limited

The Kyoto Protocol, if it has been fully implemented would have only constrained a projected 2 celsius rise in CO2 by 2050 by just 0.06 degrees. At the outset policy-makers knew it would be 97% worthless, yet still went ahead anyway.

Continued support for Kyoto must disregard the latest opinions of climate science, economic theory, and the practical problems of public policy-making. Continued support must implicitly support the investment banks to make profits at the expense of ordinary folk, and numerous fraudsters. You must also support a policy that was pretty close to useless at the outset, and now is positively harmful.