Last month Geoff Chambers posted “Who’s Binary, Us or Them? Being at cliscep the question was naturally about whether sceptics or alarmists were binary in their thinking. It reminded me about something that went viral on youtube a few year’s ago. Greg Craven’s The Most Terrifying Video You’ll Ever See.

“Which is the more acceptable risk?

- Do nothing and accept the potential catastrophe of global warming?

- Take action now, potentially harming the economy, but averting potential catastrophe?”

To his credit, Greg Craven in introducing both that human-caused climate change can have a trivial impact recognize that mitigating climate (taking action) is costly. But for the purposes of his decision grid he side-steps these issues to have binary positions on both. The decision is thus based on the belief that the likely consequences (costs) of catastrophic anthropogenic global warming then the likely consequences (costs) of taking action. A more sophisticated statement of this was from a report commissioned in the UK to justify the draconian climate action of the type Greg Craven is advocating. Sir Nicholas (now Lord) Stern’s report of 2006 (In the Executive Summary) had the two concepts of the warming and policy costs separated when it claimed

Using the results from formal economic models, the Review estimates that if we don’t act, the overall costs and risks of climate change will be equivalent to losing at least 5% of global GDP each year, now and forever. If a wider range of risks and impacts is taken into account, the estimates of damage could rise to 20% of GDP or more. In contrast, the costs of action – reducing greenhouse gas emissions to avoid the worst impacts of climate change – can be limited to around 1% of global GDP each year.

Craven has merely simplified the issue and made it more binary. But Stern has the same binary choice. It is a choice between taking costly action, or suffering the much greater possible consequences. I will look at the policy issue first.

Action on Climate Change

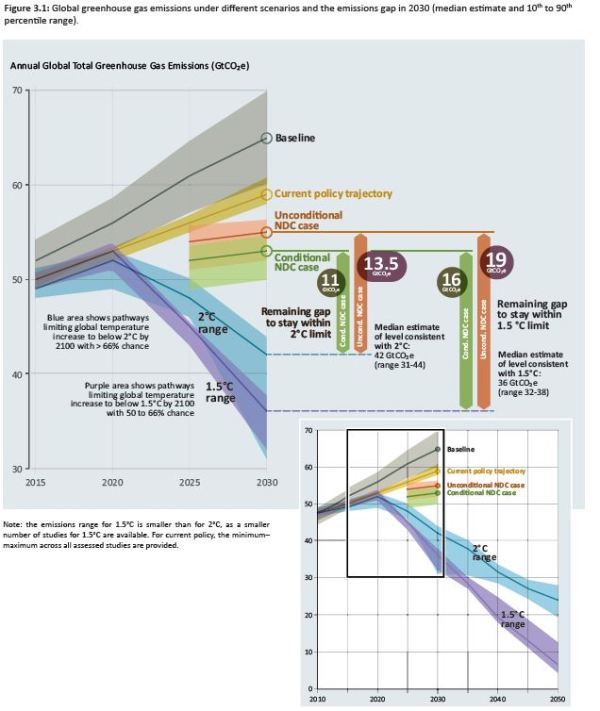

The alleged cause of catastrophic anthropogenic global warming is (CAGW) is human greenhouse gas emissions. It is not just some people’s emissions that must be reduced, but the aggregate emissions of all 7.6 billion people on the planet. Action on climate change (i.e. reducing GHG emissions to near zero) must therefore include all of the countries in which those people live. The UNFCCC, in the run-up to COP21 Paris 2015, invited countries to submit Intended Nationally Determined Contributions (INDCs). Most did so before COP21, and as at June 2018, 165 INDCs have been submitted, representing 192 countries and 96.4% of global emissions. The UNFCCC has made them available to read. So these intentions will be sufficient “action” to remove the risk of CAGW? Prior to COP21, the UNFCCC produced a Synthesis report on the aggregate effect of INDCs. (The link no longer works, but the main document is here.) They produced a graphic that I have shown on multiple occasions of the gap between policy intentions on the desired policy goals. A more recent graphic is from the UNEP Emissions Gap Report 2017, published last October and

Figure 3 : Emissions GAP estimates from the UNEP Emissions GAP Report 2017

In either policy scenario, emissions are likely to be slightly higher in 2030 than now and increasing, whilst the policy objective is for emissions to be substantially lower than today and and decreasing rapidly. Even with policy proposals fully implemented global emissions will be at least 25% more, and possibly greater than 50%, above the desired policy objectives. Thus, even if proposed policies achieve their objective, in Greg Craven’s terms we are left with pretty much all the possible risks of CAGW, whilst incurring some costs. But the “we” is for 7.6 billion people in nearly 200 countries. But the real costs are being incurred by very few countries. For the United Kingdom, with the Climate Change Act 2018 is placing huge costs on the British people, but future generations of Britain’s will achieve very little or zero benefits.

Most people in the world live in poorer countries that will do nothing significant to constrain emissions growth if it that conflicts with economic growth or other more immediate policy objectives. In terms of the some of the most populous developing countries, it is quite clear that achieving the policy objectives will leave emissions considerably higher than today. For instance, China‘s main aims of peaking CO2 emissions around 2030 and lowering carbon emissions per unit of GDP in 2030 by 60-65% compared to 2005 by 2020 could be achieved with emissions in 2030 20-50% higher than in 2017. India has a lesser but similar target of reducing emissions per unit of GDP in 2030 by 30-35% compared to 2005 by 2020. If the ambitious economic growth targets are achieve, emissions could double in 15 years, and still be increasing past the middle of the century. Emissions in Bangladesh and Pakistan could both more than double by 2030, and continue increasing for decades after.

Within these four countries are over 40% of the global population. Many other countries are also likely to have emissions increasing for decades to come, particularly in Asia and Africa. Yet without them changing course global emissions will not fall.

There is another group of countries that are have vested interests in obstructing emission reduction policies. That is those who are major suppliers of fossil fuels. In a letter to Nature in 2015, McGlade and Ekins (The geographical distribution of fossil fuels unused when limiting global warming to 2°C) estimate that the proven global reserves of oil, gas and coal would produce about 2900 GtCO2e. They further estimate that the “non-reserve resources” of fossil fuels represent a further 8000 GtCO2e of emissions. The estimated that to constrain warming to 2C, 75% of proven reserves, and any future proven reserves would need to be left in the ground. Using figures from the BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2016 I produced a rough split by major country.

Figure 4 : Fossil fuel Reserves by country, expressed in terms of potential CO2 Emissions

Figure 4 : Fossil fuel Reserves by country, expressed in terms of potential CO2 Emissions

Activists point to the reserves in the rich countries having to be left in the ground. But in the USA, Australia, Canada and Germany production of fossil fuels is not a major part of the economy. Ceasing production would be harmful but not devastating. One major comparison is between the USA and Russia. Gas and crude oil production are similar volumes in both countries. But, the nominal GDP of the US is more than ten times that of Russia. The production of both countries in 2016 was about 550 million tonnes or 3900 million barrels. At $70 a barrel that is around $275bn, equivalent to 1.3% of America’s GDP and 16% of Russia’s. In gas, prices vary, being very low in the highly competitive USA, and highly variable for Russian supply, with major supplier Gazprom acting as a discriminating monopolist. But America’s revenue is likely to be less than 1% of GDP and Russia’s equivalent to 10-15%. There is even greater dependency in the countries of the Middle East. In terms of achieve emissions targets, what is trying to be achieved is the elimination of the major source of the countries economic prosperity in a generation, with year-on-year contractions in fossil fuel sales volumes.

I propose that there are two distinct groups of countries that appear to have a lot lose from a global contraction in GHG emissions to near zero. There are the developing countries who would have to reduce long-term economic growth and the major fossil fuel-dependent countries, who would lose the very foundation of their economic output in a generation. From the evidence of the INDC submissions, there is now no possibility of these countries being convinced to embrace major economic self-harm in the time scales required. The emissions targets are not going to be met. The emissions gap will not be closed to any appreciable degree.

This leaves Greg Craven’s binary decision option of taking action, or not, as irrelevant. As taking action by a country will not eliminate the risk of CAGW, pursuing aggressive climate mitigation policies will impose net harms wherever they implemented. Further, it is not the climate activists who are making the decisions, but policy-makers countries themselves. If the activists believe that others should follow another path, it is them that must make the case. To win over the policy-makers they should have sought to understand their perspectives of those countries, then persuade them to accept their more enlightened outlook. The INDCs show that the climate activists gave failed in this mission. Until such time, when activists talk about the what “we” are doing to change the climate, or what “we” ought to be doing, they are not speaking about

But the activists have won over the United Nations, those who work for many Governments and they dominate academia. For most countries, this puts political leaders in a quandary. To maintain good diplomatic relations with other countries, and to appear as movers on a world stage they create the appearance of taking significant action on climate change for the outside world. On the other hand they are serving their countries through minimizing the real harms that imposing the policies would create. Any “realities” of climate change have become largely irrelevant to climate mitigation policies.

The Risks of Climate Apocalypse

Greg Craven recognized a major issue with his original video. In the shouting match over global warming who should you believe? In How it all Ends (which was followed up by further videos and a book) Craven believes he has the answer.

Figure 5 : Greg Craven’s “How it all Ends”

It was pointed out that the logic behind the grid is bogus. As in Devil’s advocate guise Craven says at 3:50

Wouldn’t that grid argue for action against any possible threat, no matter how costly the action or how ridiculous the threat? Even giant mutant space hamsters? It is better to go broke building a load of rodent traps than risk the possibility of being hamster chow. So this grid is useless.

His answer is to get a sense of how likely the possibility of global warming being TRUE or FALSE is. Given that science is always uncertain, and there are divided opinions.

The trick is not to look at what individual scientists are saying, but instead to look at what the professional organisations are saying. The more prestigious they are, the more weight you can give their statements, because they have got huge reputations to uphold and they don’t want to say something that later makes them look foolish.

Craven points to the “two most respected in the world“. The National Academy of Sciences (NAS) and the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS). Back in 2007 they had “both issued big statements calling for action, now, on global warming“. The crucial question from scientists (that is people will a demonstrable expert understanding of the natural world) is not for political advocacy, but whether their statements say their is a risk of climate apocalypse. These two bodies still have statements on climate change.

National Academy of Sciences (NAS) says

There are well-understood physical mechanisms by which changes in the amounts of greenhouse gases cause climate changes. The US National Academy of Sciences and The Royal Society produced a booklet, Climate Change: Evidence and Causes (download here), intended to be a brief, readable reference document for decision makers, policy makers, educators, and other individuals seeking authoritative information on the some of the questions that continue to be asked. The booklet discusses the evidence that the concentrations of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere have increased and are still increasing rapidly, that climate change is occurring, and that most of the recent change is almost certainly due to emissions of greenhouse gases caused by human activities.

Further climate change is inevitable; if emissions of greenhouse gases continue unabated, future changes will substantially exceed those that have occurred so far. There remains a range of estimates of the magnitude and regional expression of future change, but increases in the extremes of climate that can adversely affect natural ecosystems and human activities and infrastructure are expected.

Note, this is conjunction with the Royal Society, which is arguably is (or was) the most prestigious scientific organisation of them all. It is what not said that is as important as what is actually said. They are saying that there is a an expectation that extremes of climate could get worse. There is nothing that solely backs up the climate apocalypse, but a range of possibilities, including changes somewhat trivial on a global scale. The statement endorses a spectrum of possible positions that undermines the binary TRUE /FALSE position on decision-making.

The RS/NAS booklet has no estimates of the scale of possible climate catastrophism to be avoided. Point 19 is the closest.

Are disaster scenarios about tipping points like ‘turning off the Gulf Stream’ and release of methane from the Arctic a cause for concern?

The summary answer is

Such high-risk changes are considered unlikely in this century, but are by definition hard to predict. Scientists are therefore continuing to study the possibility of such tipping points beyond which we risk large and abrupt changes.

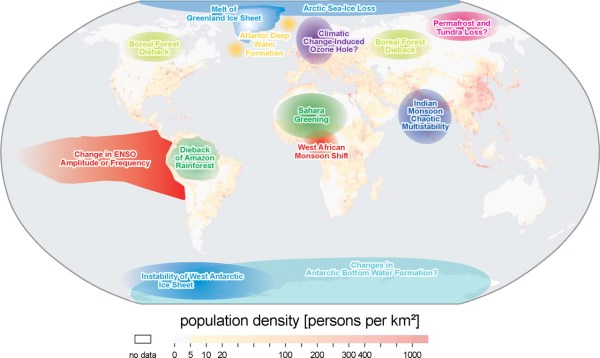

This appears not to support Stern’s contention that unmitigated climate change will costs at least 5% of global GDP by 2100. Another context of the back-tracking on potential catastrophism is to to compare with Lenton et al 2008 – Tipping elements in the Earth’s climate system. Below is a map showing the the various elements considered.

Figure 6 : Fig 1 of Lenton et al 2008, with explanatory note.

Of the 14 possible tipping elements discussed, only one makes it into the booklet six years later. Surely if the other 13 were still credible more would have been included in booklet, and less on documenting trivial historical changes.

American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) has a video

Figure 7 : AAAS “What We Know – Consensus Sense” video

It starts with the 97% Consensus claims. After asking the listener on how many, Marshall Sheppard, Prof of Geography at Univ of Georgia states.

The reality is that 97% of scientists are pretty darn certain that humans are contributing to the climate change that we are seeing right now and we better do something about it to soon.

There are two key papers that claimed a 97% consensus. Doran and Zimmerman 2009 asked two questions,

1. When compared with pre-1800s levels, do you think that mean global temperatures have generally risen, fallen, or remained relatively constant?

2. Do you think human activity is a significant contributing factor in changing mean global temperatures?

The second of these two responses was answered in the affirmative by 77 of 79 climate scientists. This was reduced from 3146 responses received. Read the original to find out why it was reduced.

Dave Burton has links to a number of sources on these studies. A relevant quote on Doran and Zimmerman is from the late Bob Carter

Both the questions that you report from Doran’s study are (scientifically) meaningless because they ask what people “think”. Science is not about opinion but about factual or experimental testing of hypotheses – in this case the hypothesis that dangerous global warming is caused by human carbon dioxide emissions.

The abstract to Cook et al. 2013 begins

We analyze the evolution of the scientific consensus on anthropogenic global warming (AGW) in the peer-reviewed scientific literature, examining 11 944 climate abstracts from 1991–2011 matching the topics ‘global climate change’ or ‘global warming’. We find that 66.4% of abstracts expressed no position on AGW, 32.6% endorsed AGW, 0.7% rejected AGW and 0.3% were uncertain about the cause of global warming. Among abstracts expressing a position on AGW, 97.1% endorsed the consensus position that humans are causing global warming.

Expressing a position does not mean a belief. It could be an assumption. The papers were not necessarily by scientists, but merely authors of academic papers that involved the topics ‘global climate change’ or ‘global warming’. Jose Duarte listed some of the papers that were included in the survey, along with looking at some that were left out.

Neither paper asked a question concerning belief in future climate catastrophism. Sheppard does not make clear the scale of climate change trends from the norm, so the human-caused element could be insignificant. The 97% consensus does not include the policy claims.

The booklet is also misleading as well in the scale of changes. For instance on sea-level rise it states.

Over the past two decades, sea levels have risen almost twice as fast as the average during the twentieth century.

You will get that if you compare the tide gauge data with the two decades of satellite data. The question is whether those two sets of data are accurate. As individual tide gauges do not tend to show acceleration, and others cannot find statistically significant acceleration, the claim seems not to be supported.

At around 4.15 in the consensus video AAAS CEO Alan I. Leshner says

America’s leaders should stop debating the reality of climate change and start deciding the best solutions. Our What we Know report makes clear that climate change threatens us at every level. We can reduce the risk of global warming to protect out people, businesses and communities from harm. At every level from our personal and community health, our economy and our future as a global leader. Understanding and managing climate change risks is an urgent problem.

The statement is about combating the potential risks from CAGW. The global part of global warming is significant for policy. The United States share of global emissions is around 13% of global emissions. That share has been falling as America’s emissions have been falling why the global aggregate emissions have been rising. The INDC submission for the United States aimed as getting US emissions in 2025 at 26-28% of 2005 levels, with a large part of that reduction already “achieved” when the report was published. The actual policy difference is likely to be less than 1% of global emissions. So any reduction in risks with respect to climate change seems to be tenuous. A consensus of the best scientific minds should have been able to work this out for themselves.

The NAAS does not give a collective expert opinion on climate catastrophism. This is shown by the inability to distinguish between banal opinions and empirical evidence for a big problem. This is carried over into policy advocacy, where they fail to distinguish between the United States and the world as a whole.

Conclusions

Greg Laden’s decision-making grid is inapplicable to real world decision-making. The decision whether to take action or not is not a unitary one, but needs to be taken at country level. Different countries will have different perspectives on the importance of taking action on climate change relative to other issues. In the real world, the proposals for action are available. In aggregate they will not “solve” the potential risk of climate apocalypse. Whatever the actual scale of CAGW, countries who pursue expensive climate mitigation policies are likely to make their own people worse off than if they did nothing at all.

Laden’s grid assumes that the costs of the climate apocalypse are potentially far greater than the costs of action, no matter how huge. He tries to cut through the arguments by getting the opinions from the leading scientific societies. To put it mildly, they do not currently provide strong scientific evidence for a potentially catastrophic problem. The NAS / Royal Society suggest a range of possible climate change outcomes, with only vague evidence for potentially catastrophic scenarios. It does not seem to back the huge potential costs of unmitigated climate change in the Stern Review. The NAAAS seems to provide vague banal opinions to support political advocacy rather than rigorous analysis based on empirical evidence that one would expect from the scientific community.

It would appear that the binary thinking on both the “science” and on “policy” leads to a dead end, and is leading to net harmful public policy.

What are the alternatives to binary thinking on climate change?

My purpose in looking at Greg Laden’s decision grid is not to destroy an alternative perspective, but to understand where the flaws are for better alternatives. As a former, slightly manic, beancounter, I would (like the Stern Review and William Nordhaus) look at translating potential CAGW into costs. But then weight it according to a discount rate, and the strength of the evidence. In terms of policy I would similarly look at the likely expected costs of the implemented policies, against the actual expected harms foregone. As I have tried to lay out above, the costs of policy and indeed the potential costs of climate change are largely subjective. Further, those implementing policies might be boxed in by other priorities and various interest groups jostling for position.

But what of the expert scientist who can see the impending on-coming catastrophes to which I am blind and to which climate mitigation will be useless? It is to endeavor to pin down the where, when, type and magnitude of potential changes to climate. With this information ordinary people can adjust their plans. The challenge for those who believe there are real problems is to focus on the data from the natural world and away from inbuilt biases of the climate community. But the most difficult part is from such methods they may lose their beliefs, status and friends.

First is to obtain some perspective. In terms of the science, it is worth looking at the broad range of different perspectives on the Philosophy of Science. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy article on the subject is long, but very up to date. In the conclusions, the references to Paul Hoyningen-Huene’s views on what sets science apart seems to be a way out of consensus studies.

Second, is to develop strategies to move away from partisan positions with simple principles, or contrasts, that other areas use. In Fundamentals that Climate Science Ignores I list some of these.

Third, in terms of policy, it is worthwhile having a theoretical framework in which to analyze the problems. After looking at Greg Craven’s video’s in 2010, I developed a graphical analysis that will be familiar to people who have studied Marshallian Supply and Demand curves of Hicksian IS-LM. It is very rough at the edges, but armed with it you will not fall in the trap of thinking like the AAAS that US policy will stop US-based climate change.

Fourth, is to look from other perspectives. Appreciate that other people might have other perspectives that you can learn from. Or alternatively they may have entrenched positions which, although you might disagree with, are powerless to overturn. It should then be possible to orientate yourself, whether as an individual or as part of a group, towards aims that are achievable.