The previous posting developed a simple graph showing the consensus case for climate change mitigation. This posting looks at the policy arguments, suggesting a huge gap between what is believed to be theoretically possible and what may be realistically achieved. The conclusion is stark. Mitigation policy optimization requires a political process that cannot deliver a result that will leave the world better for future generations.

The Mitigation Cost Curve

The previous posting presented in graphical form the consensus argument (UN IPCC & Stern) for stabilizing CO2 at around double the pre-industrial level, along with stabilizing other greenhouse gas emissions. That is that the costs of constraining the growth in levels of CO2 – are much less than the costs of allowing greenhouse gases temperature rises to go unchecked. Mitigation is essentially a cost minimization strategy with the Stern Review claims the benefits outweigh the costs 5 to 20 times. To put this into context, the Review states that the expected mean costs of mitigation will be annually 1% of annual global product (GWP). The costs of the actual climate change impact could be 5% of GDP or more.

The Prudent approach from this graph is to aim for point P. That is not the absolute minimum costs, but still much lower cost than the likely costs of doing nothing.

What is important to note is that the policy is not to reduce CO2 levels from the current levels of around 380ppm, but to stabilize the growth in emissions. This growth in emissions will come from the emerging economies, in particular from China where emissions per capita have recently been growing by 12% a year. The OECD countries have had largely static emissions per capita, and the population is very slow growing as well.

To turn theory into successful stabilization of CO2 at 550 to 600ppm, requires quite a extended process. I have attempted to break down this process into a flow chart showing the major steps. Next to each step is an arrow suggesting the direction the curve will move if the process is less than perfect.

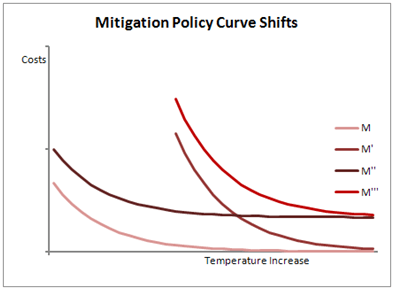

The graph below shows the impact on the mitigation curve of a movement in the arrows.

A movement to the right will shift the curve from M to M’. This is when the marginal costs increase. A movement upwards will shift the curve from M to M”. This is when costs are incurred that totally ineffective in influencing on CO2 levels. Finally there are policy shifts upwards and to the right, from M to M”’, which is a combination of higher marginal costs and ineffective elements.

Looking at the issues in turn.

Economic Theory

I will assume that the shape and position of the curve is correct. That is, there is a set of policies or actions in the real world that if applied will achieve the outcomes desired. However, these have to be discovered. Some low-cost constraints will be quite easy to discover. Others might be more difficult, relying on estimates from self-interested parties. The optimal policies will not be given for long periods, but could change over time with relative costs and technological advances. For instance, a technological breakthrough enabling much cheaper and compact batteries could transform the viability of electric cars. Therefore the switch from gasoline and diesel could be achieved with little or no subsidies.

A second assumption is that although the right economic policies will cost money, the optimal policies will have absolutely no impact on economic growth. This is a crucial assumption of the Stern Review. The policy costs will amount to around 1% of GDP at the end of the century, against costs of around 5% of GDP of climate change impacts if nothing is done. However, if growth rates are reduced by just 0.1% then in ninety years output will be over 9% lower. It is quite conceivable that a drastic change in climate policy would reduce China’s growth rate by 0.5%. By 2100 this would mean output was a full 35% lower than without the policy change. If growth by then has slowed to 3% per annum, living standards would lag 25 years, or a generation, behind where they would have been. Even if the 0.5% growth reduction is for just the first 40 years, output is still 17% lower. There may be a preference of trading a 9% lower living standards with certainty, to possible suffering from the harmful and random effects that will costAny policy that fails to recognize this

Equity

A simplistic analysis would take into account the actual costs. The cheapest ways to constrain growth in emissions is to impose a uniform policy globally. A country like Ethiopia, for instance, has nominal GDP per capita of less than 1% of the OECD average ($330 against $39473) according to World Bank Data. The real impact of a uniform carbon tax will be disproportionately felt by the poorest. The UNIPCC and Stern recognize this, but have not made an adequate provision allowance. The proposals are for the rich countries bear the overwhelming burden of the constraint in emissions and for monetary transfers to enable the poorest to grow economically without increasing their CO2 emissions. Stern recommends that the rich countries reduce their emissions by 80% per capita by 2050. However, this split will not be totally equitable. Within countries there are large inequalities in income and wealth. For instance, the richest 10% in Brazil have far better life styles than the poorest 10% in the United States. Any split between countries will leave many of the rich and powerful untouched by the policies, whilst leaving the poor in the OECD countries worse off.

Policy Identification

There are a number of possible tools to achieve a cost effective containment of CO2 growth. These include Cap and Trade; Carbon Taxes; encouraging technological development; carbon sequestration; building (or regulating the building of) new carbon-neutral power stations; and promoting energy saving through subsidies and regulation. Minimizing the costs and maximising the effectiveness of this containment requires optimizing these alternatives in terms of extent, combination and timeliness. As we do not know when to use each of these in terms of time and place, there needs to be learning through experience. When policies or initiatives are not producing results, there needs to be quick and decisive actions in constraining, changing or abandonment. Yet these decisive decisions need to be taken in the context of often only vaguely perceiving, even retrospectively, whether we are taking the best course of actions. Are we pursuing the right sort of alternative power supply? Is funding for our favoured form of future technology the correct one? If that technological preference is broadly the best are we favouring the best approach, or disregarding a far more efficient alternative? Are we applying Cap and Trade too far, or is the design of the policy inappropriate to achieve optimal result? Are any carbon taxes delivering reductions in CO2 with our cost constraints?

If we fail to optimize then policies like Cap and Trade will generate marginal costs much higher than planned. The curve shifts to the right. If the research for new low-cost carbon neutral energy consumption fails, then the curve shifts upward as we waste money. So overall, sub-optimal policy choice will shift the curve upwards and to the right.

International Negotiation

Climate change policies need to be spread broadly to be effective. If major countries are excluded, then the burden of constraint on the others will be that much greater. Yet mitigation policy is to inflict some costs now to avoid much greater costs in two, five or twenty generations down in the future. To get

- Overstate the urgency and the extent of the problem.

- Understate or fudge the immediate cost implications.

- Alienate any who raise the slightest question about the efficacy of such agreements. There are plenty of NGOs to do this.

- Understate the alternatives.

- Provide a world stage for the leaders, including those would normally be ostracized. (Such as here and here).

- Leave aside the implementation problems.

International Polices & Targets

The fudging is likely to affect the final policy. Nation states do not accept strict targets within cost constraint, with punishments meted out to those that fail. They will not relinquish part of their sovereignty and possibly their economic growth easily. But the poorer ones, with promises of cash to help them out, will be enthusiastic. Therefore any final agreement will load costs on those keenest on the policy, and plenty of loop-holes to allow those with other priorities, or those with a weak political grasp on power, to fudge. This does not have to be a permanent fudge

National Policies

There will be a number of different approaches. Cutting or CO2 levels or constraining the growth requires long-term policies, with short-term plaudits. In Britain’s case the implementation CO2 reduction target of 80% gained much praise in the international community. But the costs are mostly left to successor governments. The favoured form of green energy is easy to promote, but the rising energy costs and the prospect of future energy blackouts on windless and frost winter nights will be blamed on later governments.

In the short-term there may be some job benefits and subsidies. Promoting Cap and Trade will create jobs for those administering the scheme and large profits for those who can easily reduce their emissions and sell on the carbon credits. There are also jobs to be had in climate research and the development of new technologies.

There is also political benefit to be had from providing a reason to raise taxes. In Britain the green taxes have mostly been loaded onto the motorist. Yet such a policy is likely to have very little marginal impact on CO2 emissions for precisely them same reason that it is a very good way of raising extra tax revenue – demand is very inelastic with respect to price. It is only with viable and cost-effective substitutes (electric to replace the internal combustion engine) that we will see a switch.

The nature of deriving and maintaining political census will be to have little project management from the top down. Therefore, there will be initiatives that were sub-optimal to start with and less effective moving forward. There will be little focus on research, but plenty on public relations. Rather than maximizing effectiveness and minimizing costs, there will be other, self-justifying matrices developed. The biggest justification will be international obligations.

Policy Outcomes and Policy Feedbacks

There may be plenty of policy and much more rhetoric, but the policy outcomes are likely to be feeble at great cost. However, to obtain and maintain the optimal policies, there must be a feedback process. This feedback needs to influence every level, including the economic theory as shown below.

This needs to be a continual and dynamic process. For this to happen there needs to be objective and honest analysis of results to better refine and amend our view of the optimal policies at both national and international level. The size of the arrows indicates my personal assessment of the importance of each aspect. The biggest feedback is in the continuous altering of national policies, to bring into line with optimal policies. But there must be an ability to easily change course at all levels. This requires not just openness and flexibility, but surrender of policy in this area to an international body. But countries will not easily agree to shoulder more of the burden, or lose subsidies. They will not easily be told that they must change course. Vested interests in the environmental matters do not have a unique humility and objectivity that is absent in other groups. Neither will politicians easily admit that they have made errors of judgment, or that there are areas where they have neither the competency nor power to act upon.

Conclusion

The process of implementing an optimal policy, requires an openness and flexibility that does not exist. The whole policy process works against this. Politics is about negotiation and compromise between competing interests. It is about jostling for power, rewarding supporters and undermining the influence of opponents. It is also about other priorities as well, which in the short-term are more pressing. In the section on economic theory we I showed how a small reduction in economic growth can more than offset the worst consequences of the policy.

The problem now becomes two-fold.

- Guaranteeing how the revised optimal policy P”’ will be less costly than doing nothing and letting the total climate impact costs reach CCImax.

- Justifying to the developed nations why they should be significantly worse off than doing nothing.

In the next posting I will look at the validity of the estimation of the costs of climate change.

Dave Worley

/ 28/02/2011Social Security has barely worked for three generations.

We have no right to plan for more than one generation ahead.