If a fantasy is something impossible, or highly improbable, then I believe that I more than justify the claim concerning the latest BP Energy Outlook. A lot of ground will be covered but will be summarised at the end.

Trigger warning. For those who really believe that current climate policies are about saving the planet, please exit now.

The BP Energy Outlook 2023 was published on 26th June. From the introduction

Energy Outlook 2023 is focused on three main scenarios: Accelerated, Net Zero and New Momentum. These scenarios are not predictions of what is likely to happen or what BP would like to happen. Rather they explore the possible implications of different judgements and

assumptions concerning the nature of the energy transition and the uncertainties around those judgements.

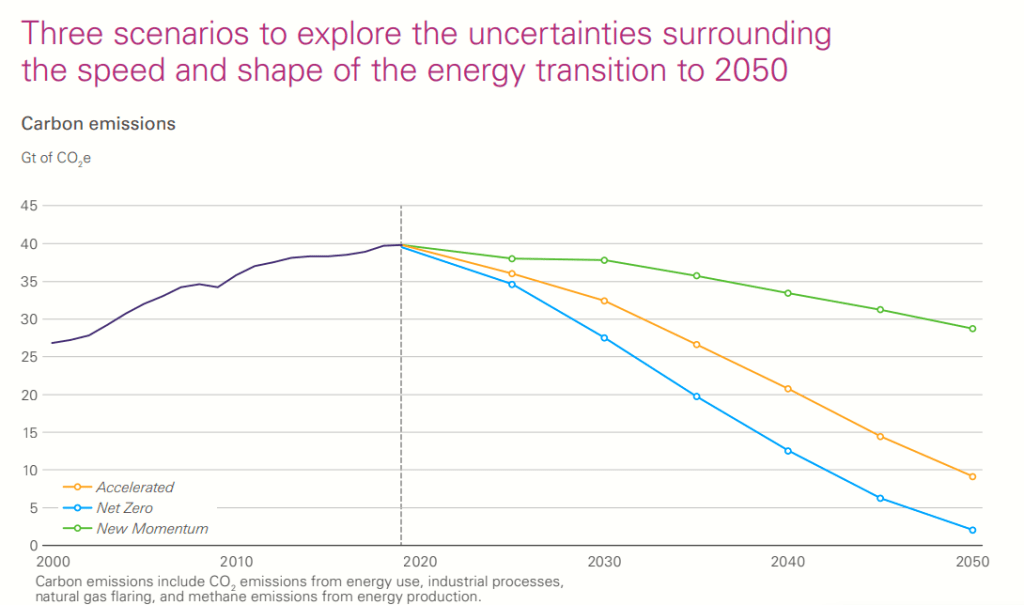

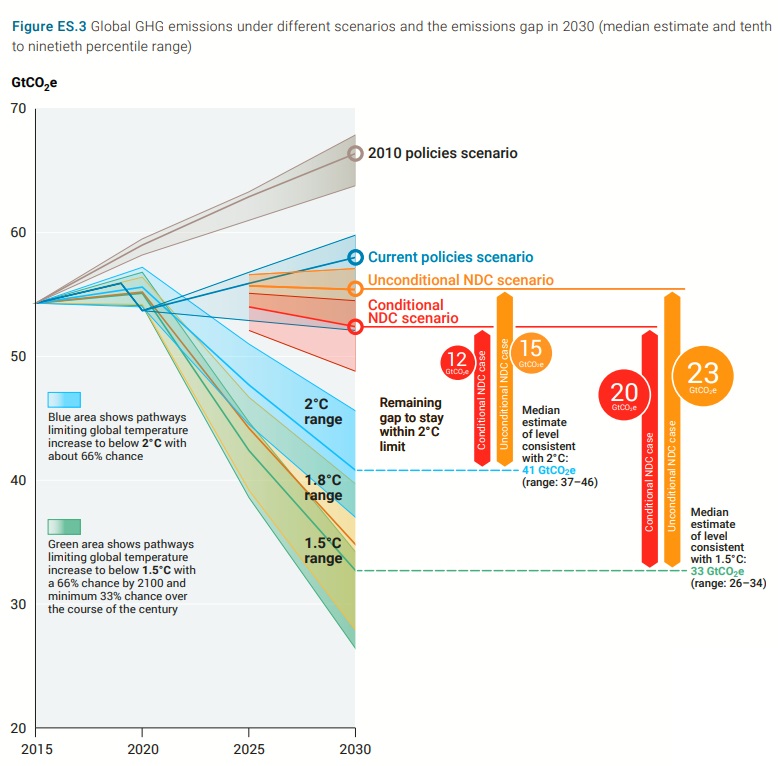

One might assume that the order is some sort of ascent, or decent. That is not the case, as New Momentum is the least difficult to achieve, then Accelerated, with Net Zero being the hardest to achieve. The most extreme case is Net Zero. Is this in line with what is known as Net Zero in the UNFCCC COP process? From the UNEP Emissions Gap Report 2018 Executive Summary, major point 2

Global greenhouse gas emissions show no signs of peaking. Global CO2 emissions from energy and industry increased in 2017, following a three-year period of stabilization. Total annual greenhouse gases emissions, including from land-use change, reached a record high of 53.5 GtCO2e in 2017, an increase of 0.7 GtCO2e compared with 2016. In contrast, global GHG emissions in 2030 need to be approximately 25 percent and 55 percent lower than in 2017 to put the world on a least-cost pathway to limiting global warming to 2°C and 1.5°C

respectively.

With Net Zero being accomplished for 2°C in 2070 and 1.5°C in 2050, this gives 20 years of 2017 emissions from 2020 for 2°C of warming and just 12 years for 1.5°C. Figure 1 in the BP Energy Outlook 2023 Report, reproduced below, is roughly midway between 12 and 20 years of emissions, although with only about three-quarters of the emissions, in equivalent CO2 tonnes that the UN uses for policy. This seems quite reasonable course to take to keep things simple.

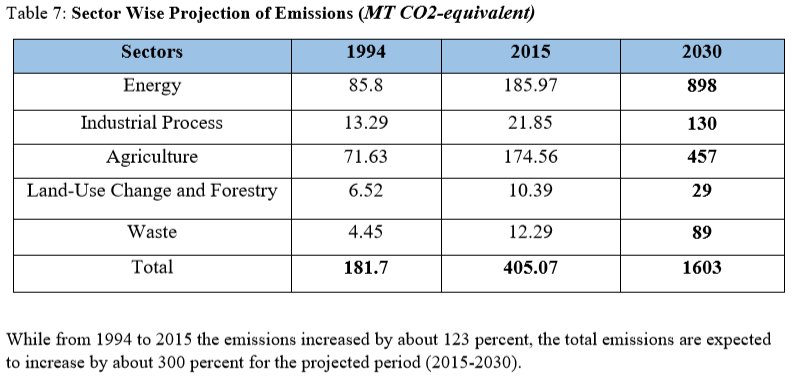

The BP Energy Outlook summarises the emissions pathways in a key chart, reproduced below.

One would expect the least onerous scenario would be based on current trends. The description says otherwise.

New Momentum is designed to capture the broad trajectory along which the global energy system is currently travelling. It places weight on the marked increase in global ambition

for decarbonization in recent years, as well as on the manner and speed of decarbonization seen over the recent past. CO2e emissions in New Momentum peak in the 2020s and by 2050 are around 30% below 2019 levels.

That is the most realistic scenario based on current global policies is still based on a change in actual policies. How much though? Fig 1 above, shows, actual emissions up to 2019 are increasing, then a decrease in all three scenarios from 2020 onwards.

At Notalotofpeopleknowthat, in an article on this report, the slightly narrower CO2 emissions narrow CO2 emissions are shown.

There was a significant drop in emissions in 2020 due to covid lockdowns, but emissions more than recovered to break new records in 2022. But all scenarios in Fig 1 show a decline in emissions from 2019 to 2025. Neither do emissions show signs of peaking? The UNEP Emissions GAP Report 2022 forecasts that GHG emissions (the broadest measure of emissions) could be up to 9% higher than in 2017, with a near zero chance of being the same. The key emissions gap chart is reproduced in Fig 3.

Clearly under current policies global GHG emissions will rise this decade. The “new momentum” was nowhere in sight last October, nor was there any sight of emissions peaking after COP27 at Sharm el-Sheikh in December. Nor is there any real prospect of that happening at COP28 in United Arab Emirates (an oil state) later this year.

Yet even this chart is flawed. The 2°C main target for 2030 is 41 GtCO2e and the 1.5°C main target is 33 GtCO2e. Both are not centred in their ranges. From the EGR 2018, a 25% reduction on 53.5 is 40, and a 55% reduction 24. But at least there is some pretence of trying to reconcile desired policy with the most probable reality.

It gets worse…

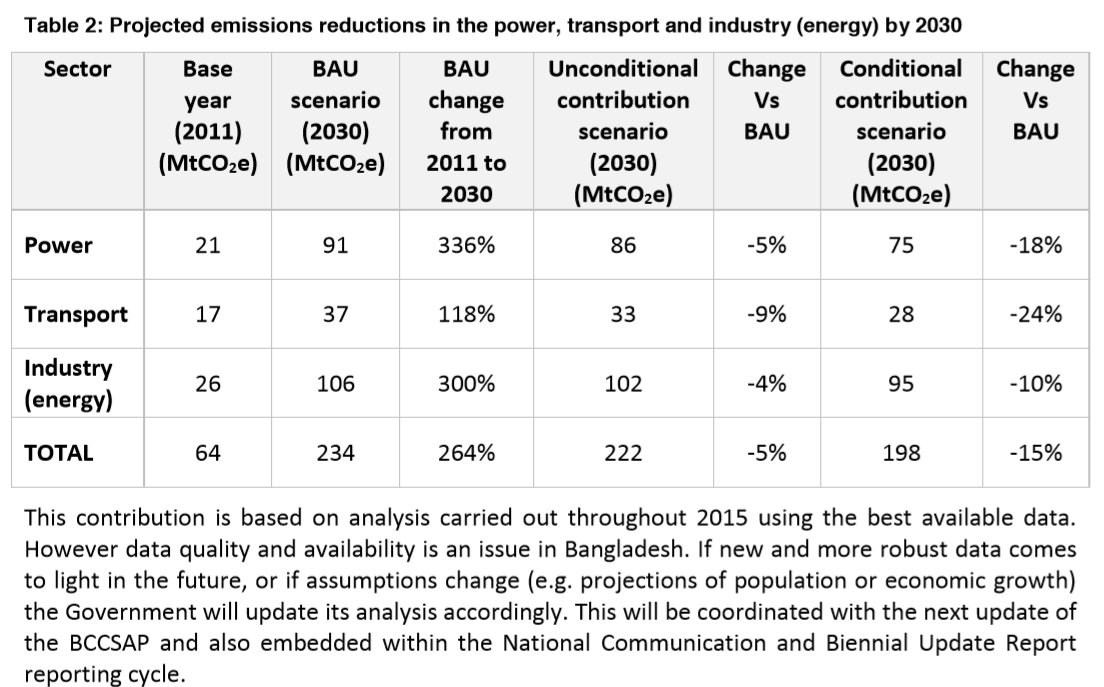

In the lead-up to COP21 Paris 2015 countries submitted “Intended Nationally Determined Contributions” (INDCs). The UNFCCC said thank you and filed them. There appears to be no review or rejection of any INDCs that clearly violated the global objective of substantially reducing global greenhouse gas emissions by 2030. Thus an INDC was not rejected in the contribution was highly negative. That is if the target implied massively increasing emissions. The major example of this is China. Their top targets of peaking CO2 emissions around 2030 & “to lower carbon dioxide emissions per unit of GDP by 60% to 65% from the

2005 level” (page 21) can be achieved even if emissions more than double between 2015 and 2030. This is simply based on the 1990-2010 GDP average growth of 10% and the emissions growth of 6%. Both India and Turkey (page 5) plan to double emissions in the same period. (page 5) and Pakistan to quadruple theirs (page 26). Iran plans to cut its emissions by 4% up to 2030 compared with a BAU scenario. Which is some sort of increase.

There are plenty of other non-OECD countries planning to increase their emissions. As of mid-2023 no major country seems to have reversed course. Why is this important? The answer lies in a combination of the Paris Agreement & the data

The flaw in the Paris Agreement

Although nearly every country has signed the Paris Agreement, few have understood its real lack of teeth in gaining reductions in global emissions. Article 4.1 states

In order to achieve the long-term temperature goal set out in Article 2,

Parties aim to reach global peaking of greenhouse gas emissions as soon as

possible, recognizing that peaking will take longer for developing country Parties,

and to undertake rapid reductions thereafter in accordance with best available

science, so as to achieve a balance between anthropogenic emissions by sources

and removals by sinks of greenhouse gases in the second half of this century, on the

basis of equity, and in the context of sustainable development and efforts to

eradicate poverty.

The agreement lacks any firm commitments but does make a clear distinction between developed and developing countries. The latter countries have no obligation even to slow down emissions growth in the near future. Furthermore, the “developed” countries are quite small in population. These are basically all the members of the OECD. This includes some of the upper middle-income countries like Turkey, Costa Rica and Columbia, but excludes the small Gulf States with very high per capita incomes.

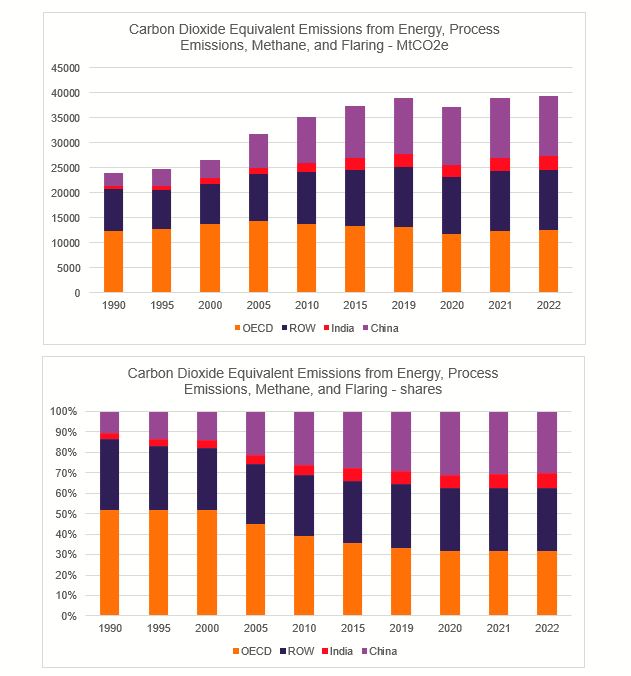

BP is perhaps better known for its annual Statistical Review of World Energy. The 2023 edition was published on the same day as the Energy Outlook but for the first time by the Energy Institute. From this, I have used the CO2 emissions data to split out the world emissions into four groups – OECD, China, India, and Rest of the World. The OECD countries collectively have a population of about 1.38bn, or about the same as India or China.

From 1990 to 2022, OECD countries increased their emissions by 1%, India by 320%, China by 370% and ROW by 45%. As a result the OECD share of global emissions fell from 52% in 1990 to 32%. Even if all the non-OECD countries kept the emissions constant in the 2020s, the 2°C target could only be achieved by OECD countries reducing their emissions by nearly 80% and for the 1.5°C target by over 170%. The reality is that obtaining deep global emissions cuts are about as much fantasy as believing an Official Monster Raving Loony Party candidate could win a seat in the House of Commons. Their electoral record is here.

The forgotten element….

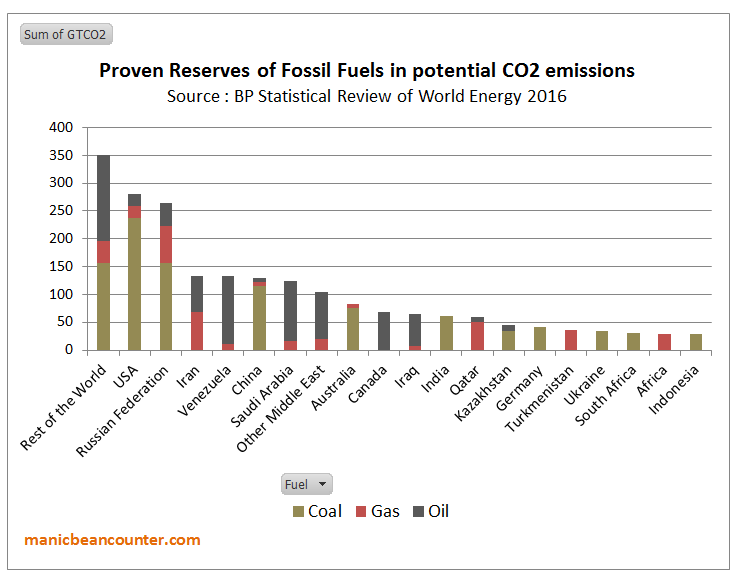

By 2050, we find that nearly 60 per cent of oil and fossil methane gas, and 90 per cent of coal must remain unextracted to keep within a 1.5 °C carbon budget.

Welsby, D., Price, J., Pye, S. et al. Unextractable fossil fuels in a 1.5 °C world. Nature 597, 230–234 (2021).

It has been estimated that to have at least a 50 per cent chance of keeping warming below 2°C throughout the twenty-first century, the cumulative carbon emissions between 2011 and 2050 need to be limited to around 1,100 gigatonnes of carbon dioxide (Gt CO2). However, the greenhouse gas emissions contained in present estimates of global fossil fuel reserves are around three times higher than this, and so the unabated use of all current fossil fuel reserves

McGlade, C., Ekins, P. The geographical distribution of fossil fuels unused when limiting global warming to 2 °C. Nature 517, 187–190 (2015).

is incompatible with a warming limit of 2°C

I am not aware of any global agreement to keep most of the considerable reserves of fossil fuels in the ground. Yet is clear from these two papers that meeting climate objectives requires this. Of course, the authors of the BP Energy Outlook may not be aware of these papers. But they will be aware of the Statistical Review of World Energy. It has estimates of reserves for oil, gas, and coal. They have not been updated for two years, but there are around 50 years of gas & oil and well over 100 years of coal left. Once

Key points covered

- Energy Outlook scenarios do not include an unchanged policy

- All three scenarios show a decline between 2019 & 2025. 2022 actual emissions were higher than 2019.

- In aggregate Paris climate commitments mean an increase emissions by 2030, something ignored by the scenarios.

- The Paris Agreement exempts developing countries from even curbing their emissions growth in the near term. Accounting for virtually all the emissions growth since 1990 and around two-thirds of current emissions makes significantly reducing global emissions quite impossible.

- Then totally bypassing the policy issue of keeping most of the available fossil fuels in the ground.

Given all the above labelling the BP Energy Outlook 2023 scenarios “fantasies” is quite mild. Even though they may be theoretically possible there is no general recognition of the policy constraints which would lead to action plans to overcome these constraints. But in the COP process and amongst activists around the world there is just a belief that proclaiming the need for policy will achieve a global transformation.

Kevin Marshall